The Death and Life of Hokkien:

Changed Your Identity and Wiped Out

Your Language

— Benedict Anderson

Introduction

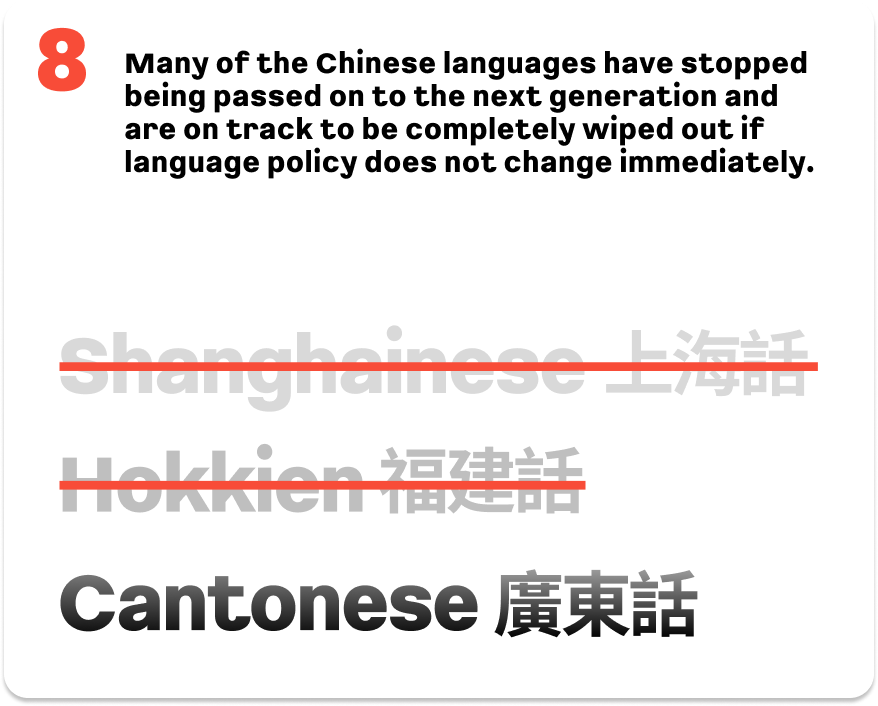

Many non-Mandarin Chinese languages such as Hokkien, Hakka, Cantonese and Teochew, are big languages with many speakers around the world. Hokkien alone has 25 million speakers; two and a half times the population of Sweden. While the Swedish language faces no threat of extinction, Hokkien is set to vanish as its speakers abandon it for Mandarin.

Many people tend to lament the death of languages with a sense of loss, and ascribes language endangerment to modernisation and globalisation as if it is a matter of course that these languages will die out.

of loss, and ascribes language endangerment to modernisation and globalisation as if it is a matter of course that these languages will die out.

In this exhibition, you will see that the root cause of decline in these languages is, in fact, an ideology, which emerged in the 19th century. This is also an exhibition that challenges our preconceived idea about Chinese.

Key Takeaway

Chapter 01

Early History

of Languages

in China

Linguists generally believe that an ancient form of Chinese was originally spoken in the Central Plain along the Yellow River. As the empire grew, the northern group intermarried with the nomadic people from the Steppe, while the southern group intermarried with the aboriginal people in southeastern China.

“The area from Kau-tsí 交趾 (northern Vietnam and southern China) to Kuè-khe 會稽 (Greater Shanghai area) stretching over seven to eight thousand lǐ (Chinese mile) are inhabited with a hundred types of Ua̍t people with a variety of surnames.”

— Book of Hàn, Geography Chapter 漢書·地理志

The indigenous peoples who occupied southern China are collectively known as the Hundred Ua̍t (百越 Baiyue). Ancient Chinese accounts often characterise these people as barbarians using stereotypes and exaggerations, and describe the indigenous people in the Hokkien region as the descendants of snakes.

百越

This can be seen from the Chinese character for Hokkien 閩 which contains a pictograph of a snake.

虫 = Snake

Snake patterns on Paiwan utensils

Both archaeological relics and historical records have indicated that the Kuínn-tang (廣東 Guangdong) region before the Bêng (明 Ming, 1368–1644) dynasty was populated with indigenous people.

The annals of the Khai-guân 開元 period (730s) say that the lands of Bân 閩 county and Uât-tsiú 越州 were anciently the lands of the Eastern Âu 東甌. The people of Kiân-tsiú 建州 and its area are all the descendants of snakes. The five surname clans, such as the Uînn 黃 and the Lîm 林, are their descendants.

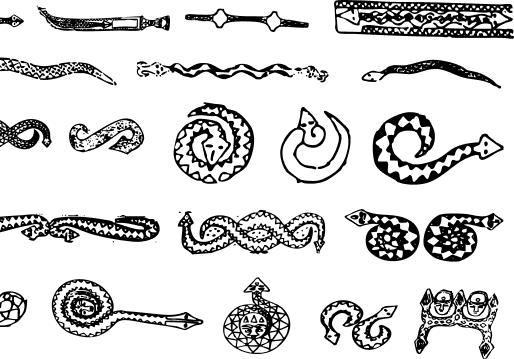

One example of a material culture of the Ua̍t 越 people, is the bronze kettledrum culture.

Bronze drums such as this one were first cast by the bronze age Tiân 滇 culture in what is now Hûn-lâm (雲南 Yunnan). From here, the drum-making tradition travelled down the Red River to the Red River Delta (Vietnam). After 43 AD, related traditions spread eastwards and southwards into the hill country in every direction (including southern China) as well as further afield into Southeast Asia.

Chinese texts from the middle of the first Millennium AD describe the drums as the prized property of local chieftains ruling over peoples known as Lí 俚 and Liau 獠.

Lí 俚 and Liau 獠 peoples were assimilated to Chinese culture over several centuries but were still recorded in the area as late as the sixteenth century.

This style of engravings can often be found on drums that have been excavated in the mountain ranges approximately half-way between Hanoi and Kuínn-tsiu (Canton). This gives us a glimpse into the material culture of southern China in ancient times. Over four hundred of these drums have been excavated to date.

It is difficult to determine if the population in southern China consists more of the descendants from the Central Plain or the aboriginal peoples. We also don’t know exactly what language they spoke, but there is evidence they were Kra-Dai, Hmong Mien and Austroasiatic speakers, based on the vocabulary and grammar these languages left to southern Chinese languages today.¹

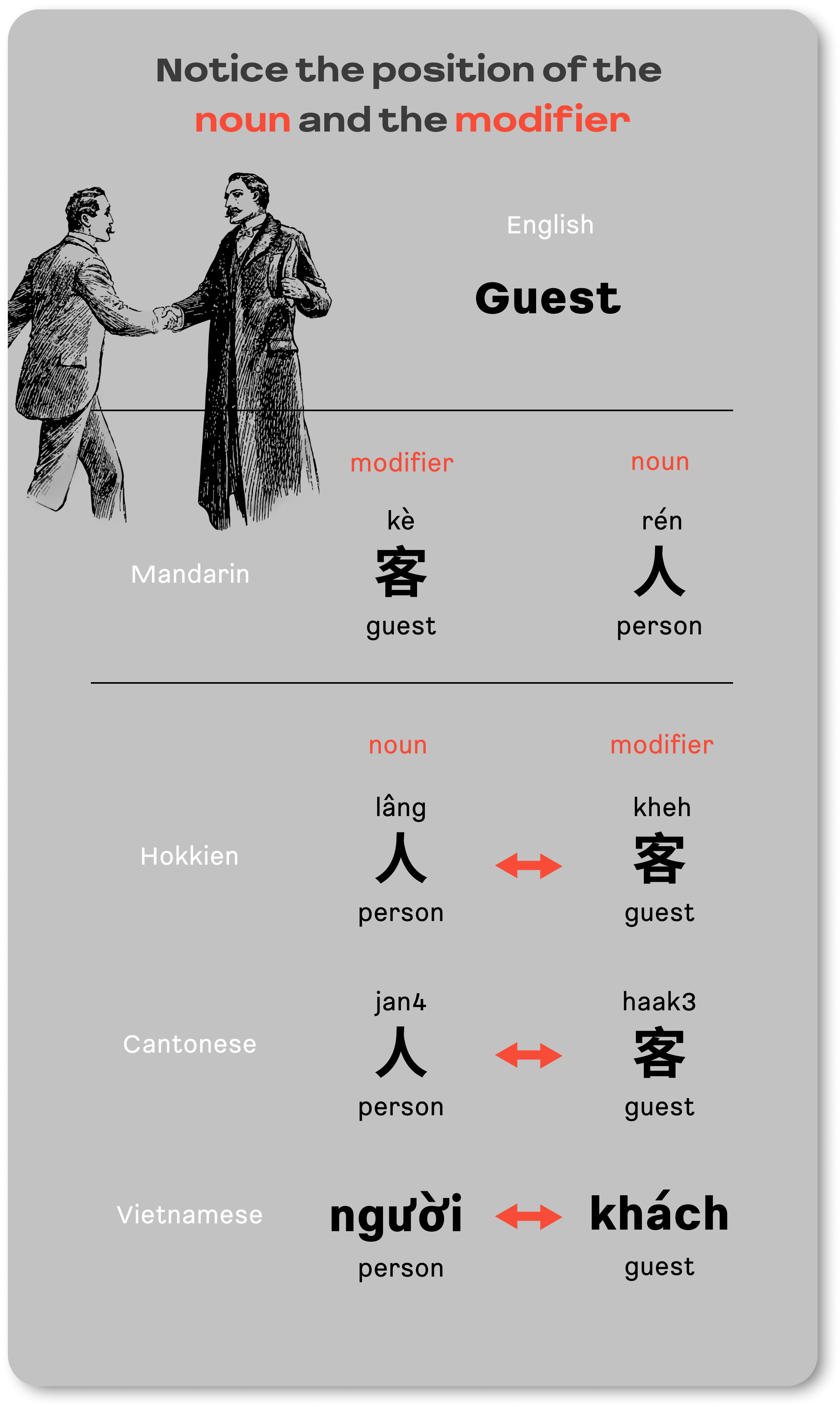

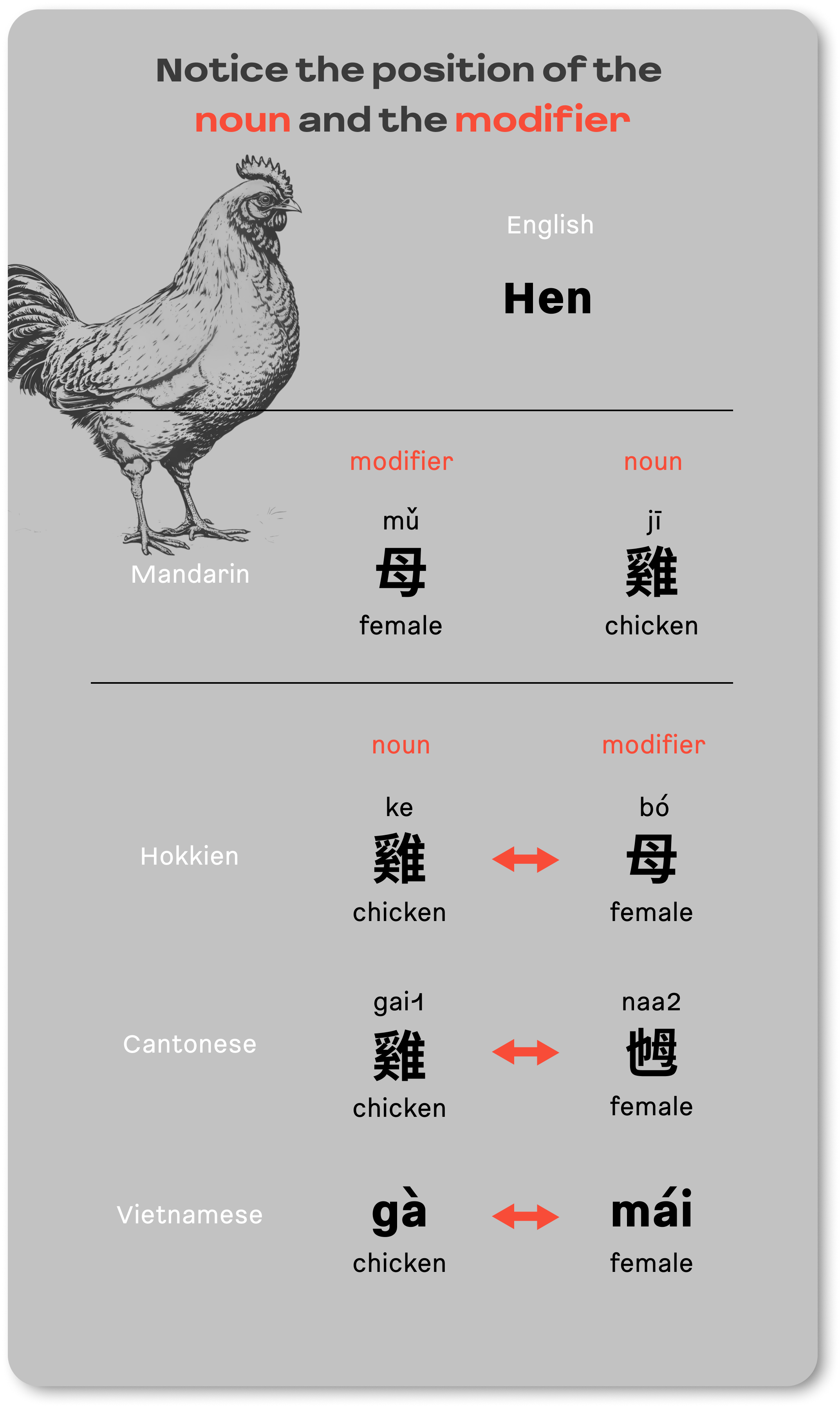

Traces of this ancient past remain in many southern Chinese languages. Comparisons made between the grammar and vocabulary of southern Chinese languages with that of their southern neighbours demonstrate a shared heritage between the southern Chinese people and Southeast Asia.

Use the arrows below to see

the difference in pronunciation

English/Malay

•

Suitable

Mandarin

•

啱

ngaam

others

适合

shì hé

•

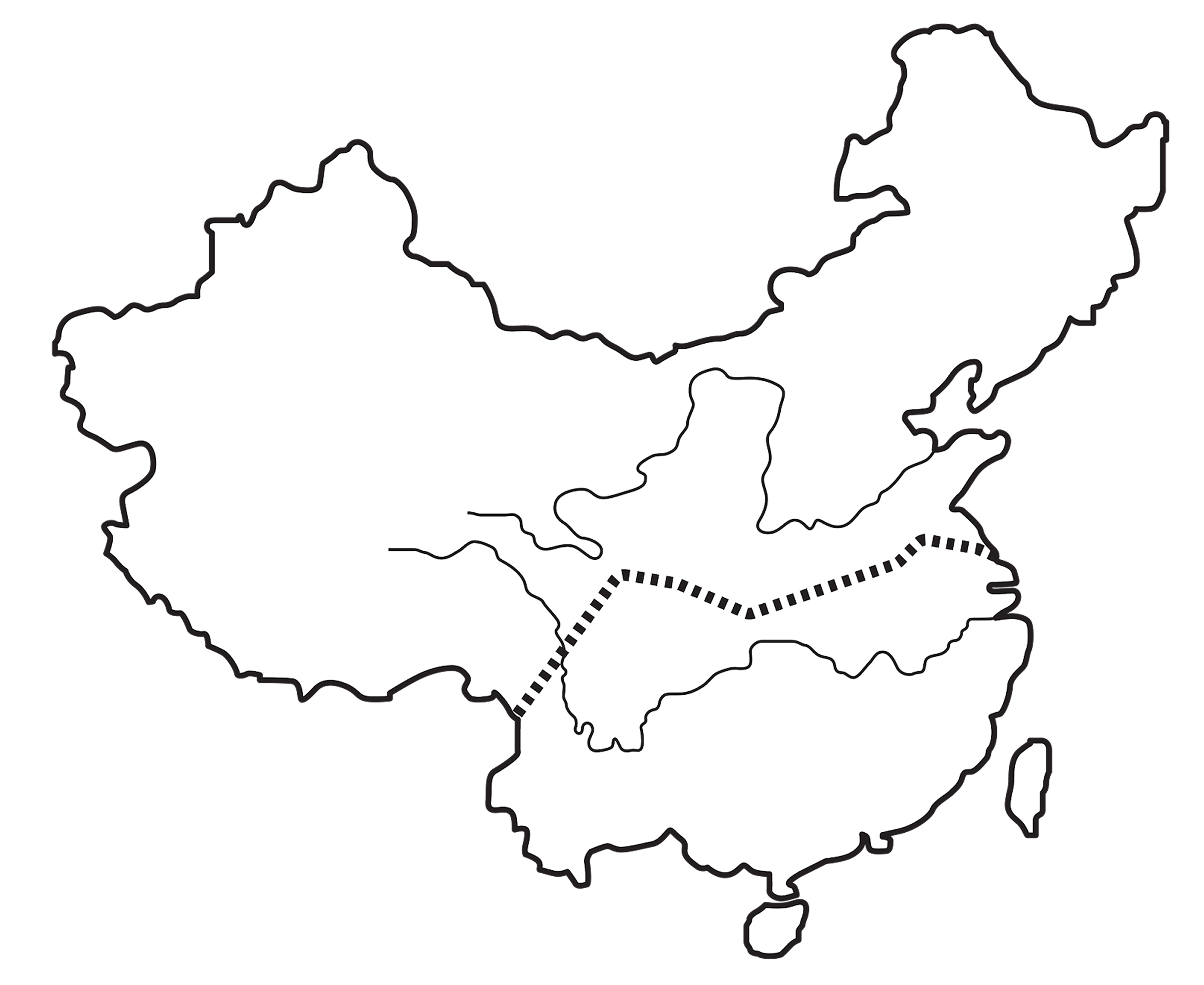

The genetic divide

between the north and south.

Genetic analysis shows a clear difference between the northern and southern populations despite the fact they are categorised as ethnic ‘Hàn’ 漢. This difference is most prominent on the maternal lineages which extend approximately along the Huâi River 淮河 and the Tsîn (秦 Qin) Mountains near to the Yangtze River.²

The Indigenous

People in

South China

The indigenous people in the south intermarried with the people from the Central Plain and were gradually absorbed into the empire. But they were by no means homogenous and the descendants of these populations did not consider each other as the same people.

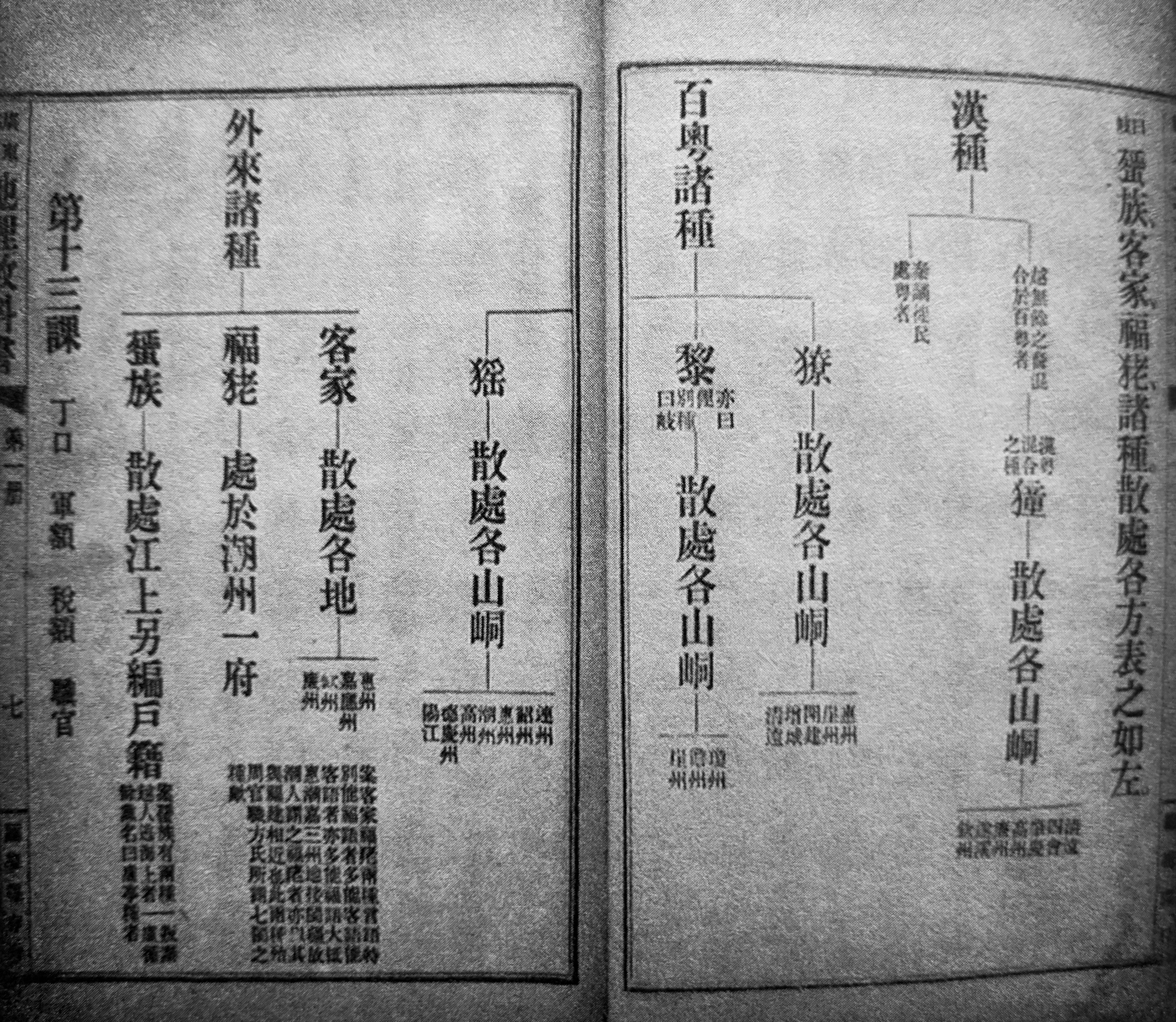

In 1907, a Cantonese scholar, Uînn Tsiat 黃節, mentioned in his textbook, Local Geography of Kuínn-tang (Guangdong) 廣東鄉土地理教科書, that “there are Hakka and Hoklo (Swabue and Teochew) people in the Kuínn-tang (Guangdong) province but they are not Cantonese and are not of the Hàn race”.

The Teochews and Hakkas were not considered ‘ethnic Hàn’ in Local Geography of Kuínn-tang (Guangdong) published in 1907.

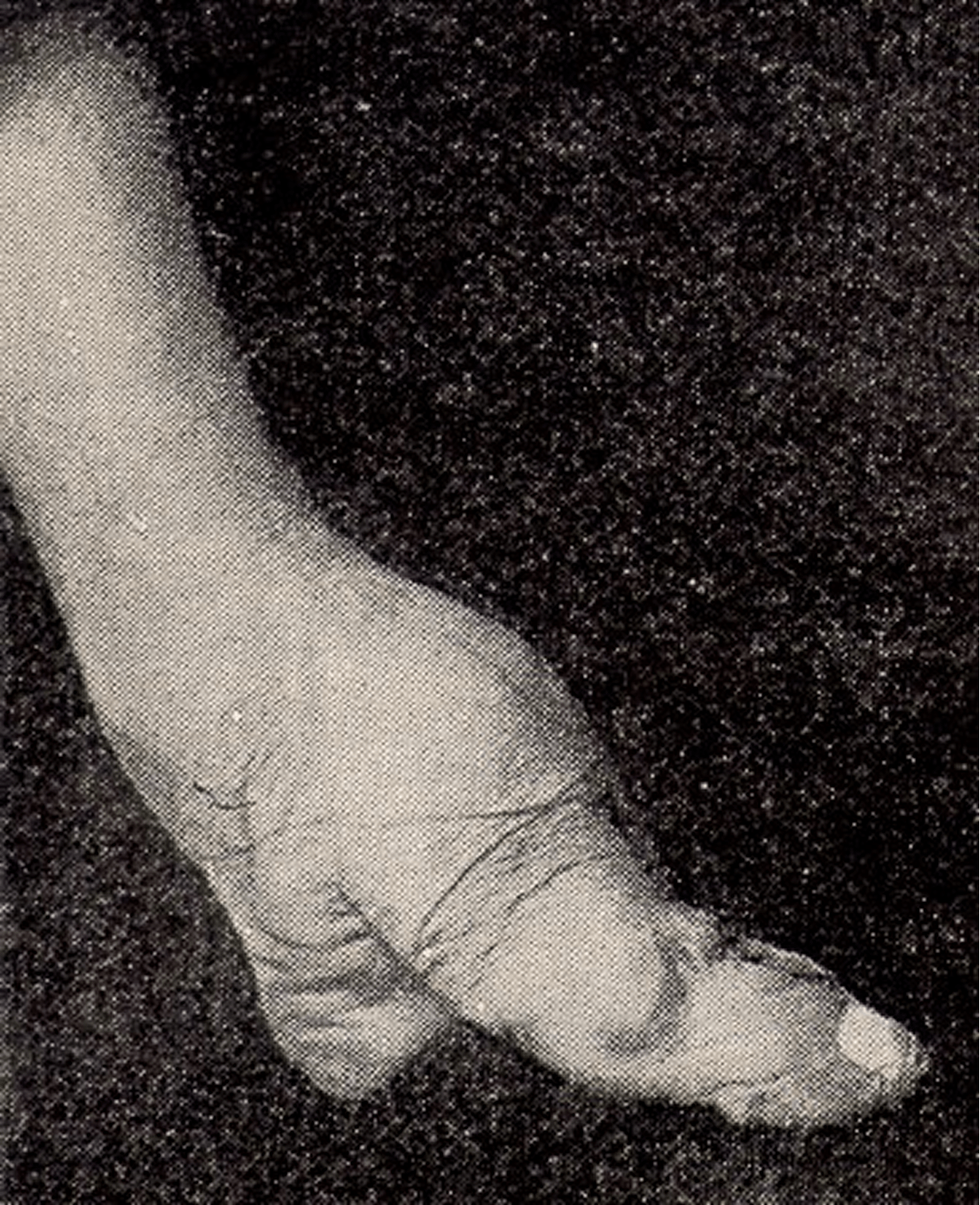

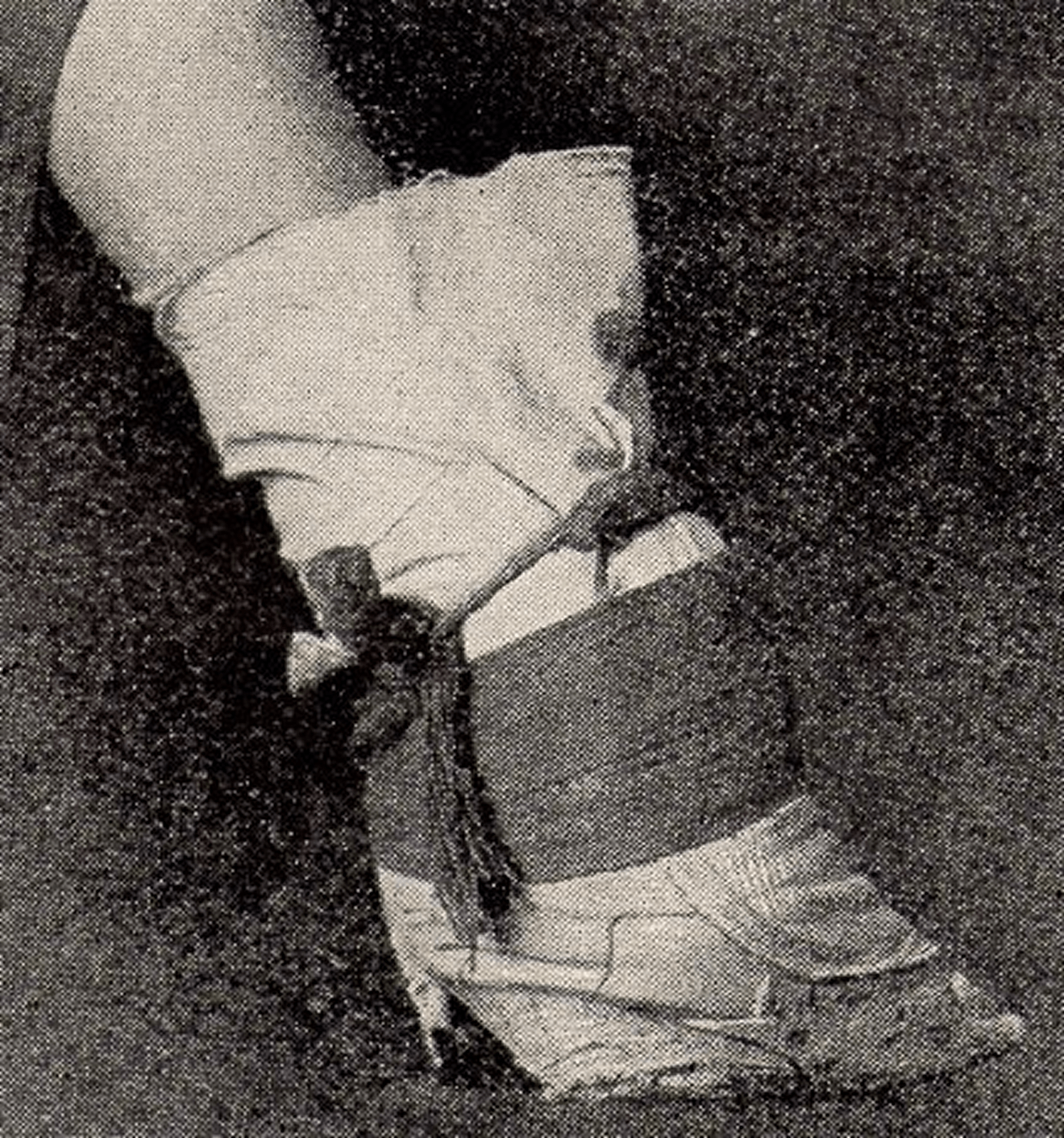

Hakka people also did not practise foot binding, a custom of binding the feet of young girls to modify the shape and size of their feet. This is a cultural distinction that sets Hakka people apart from other linguistic groups.

Chapter 02

Spoken Chinese

Languages

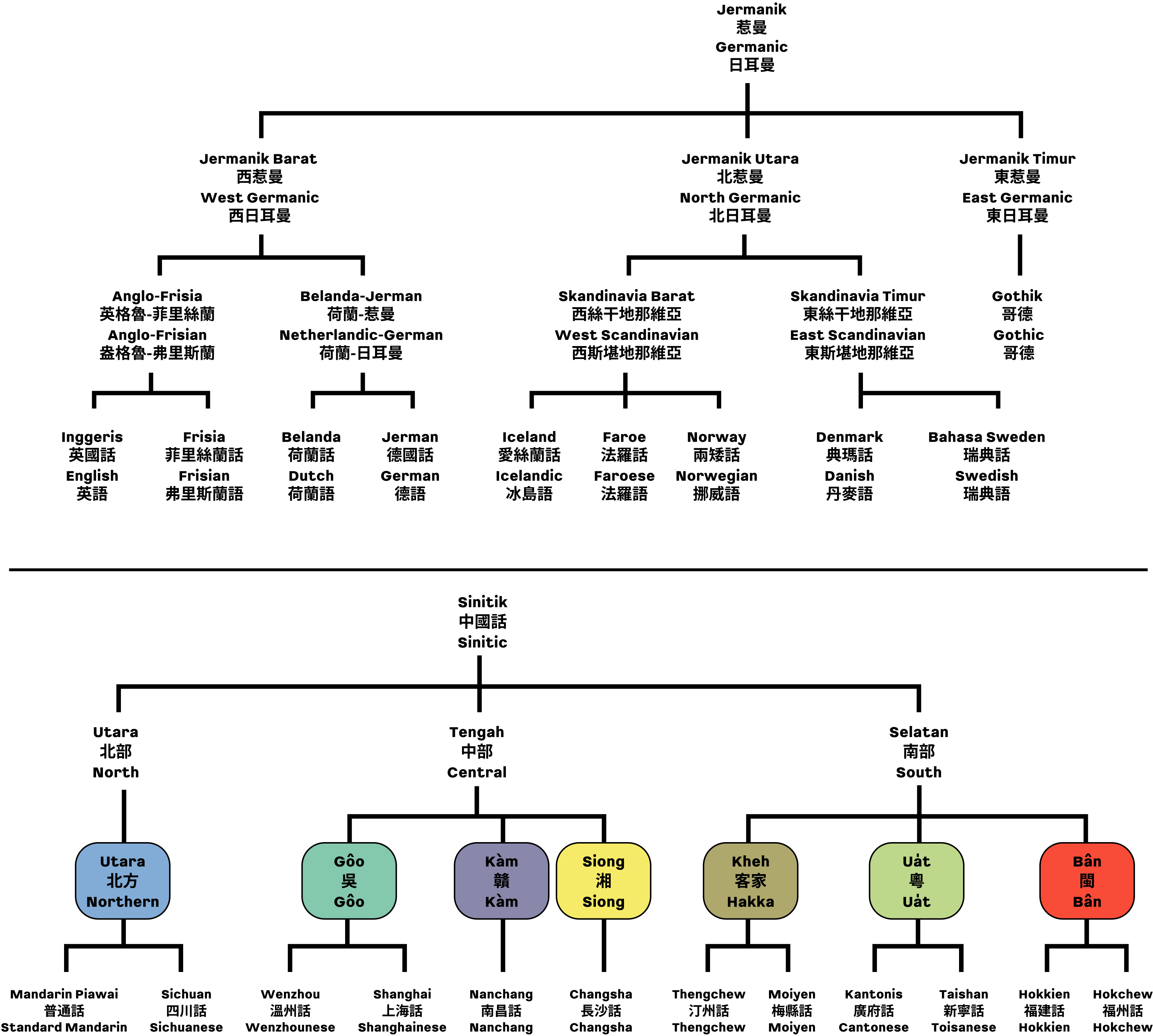

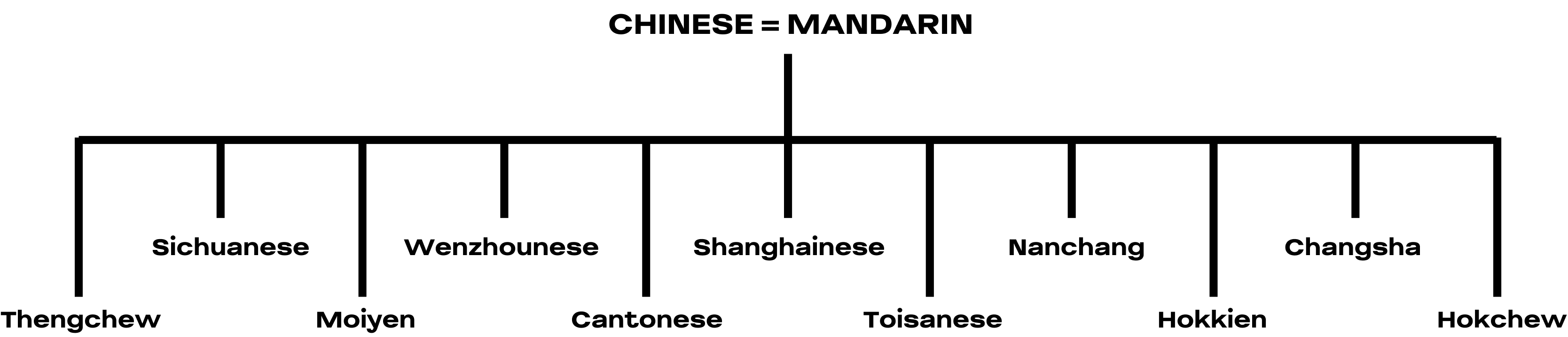

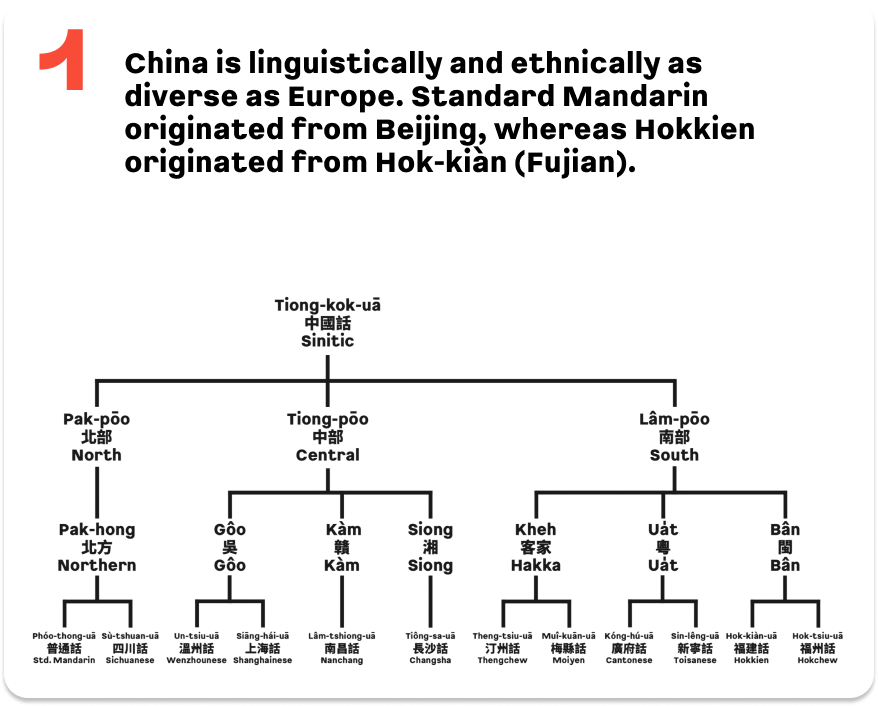

Linguists generally compare the diversity of spoken Chinese languages to the entire branch of the Germanic or Romance languages.

Simplified taxonomies of the European and Chinese languages

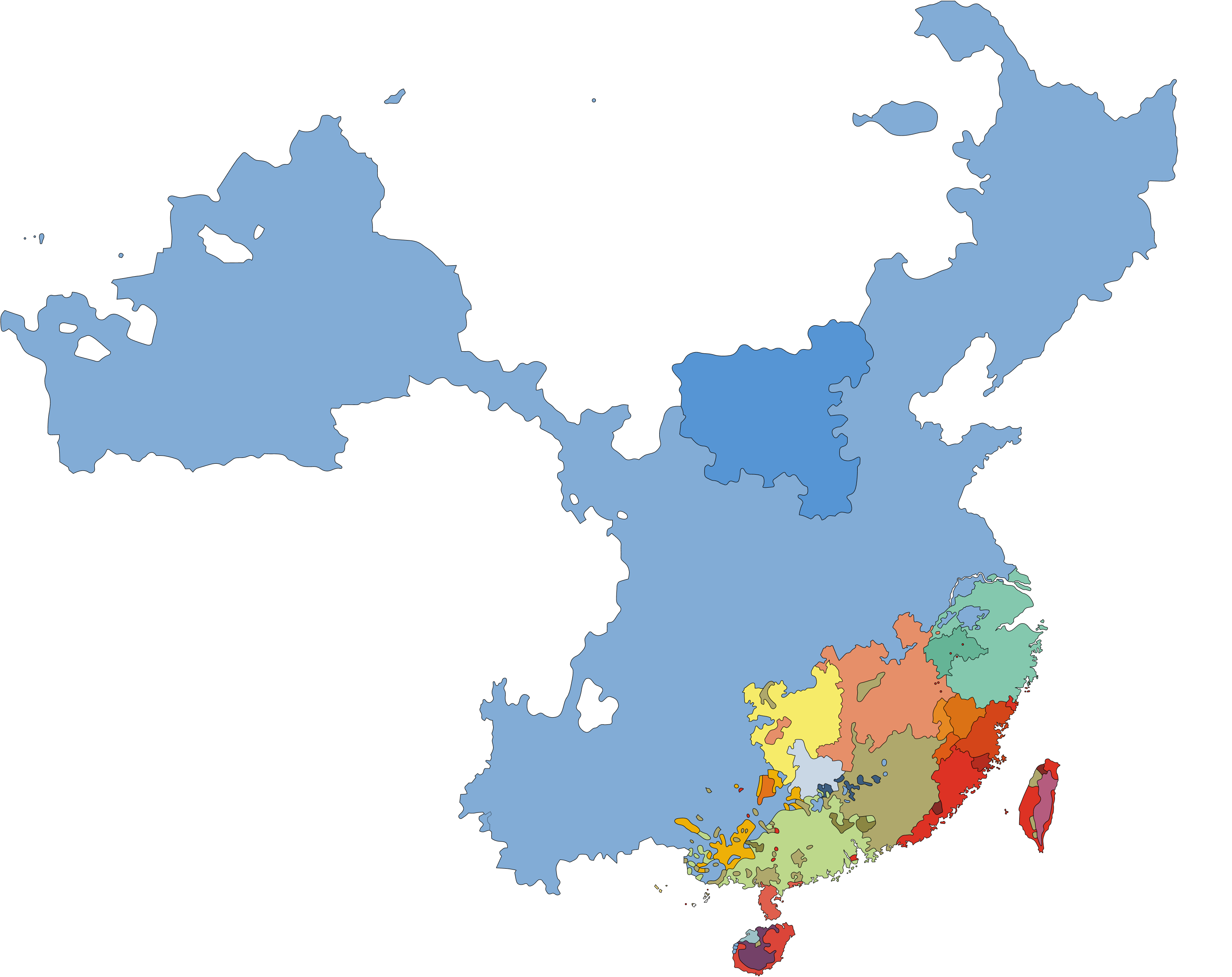

The spoken Sinitic (Chinese) languages, often referred to as ‘dialects’ 方言, can be largely categorised into seven branches; Northern or Mandarin, Gôo (吳 Wu), Kàm (贛 Gan), Siong (湘 Xiang), Hakka (客家), Ua̍t (粵 Yue) and Bân (閩 Min).

Hokkien is a language of the Bân branch, Putonghua is a language within the Northern or Mandarin branch, and Cantonese is a language within the Ua̍t branch.

How different are they?

One method to measure the similarity between two languages is by comparing cognates. Cognates are words which share the same root across two different languages. These words in English, Dutch and German are cognates as they share a common origin.

House

English

Huis

Dutch

Haus

German

Using a list of approximately 200 basic words called the Swadesh list, we can compare the percentage of cognates in each local language of several Chinese cities.

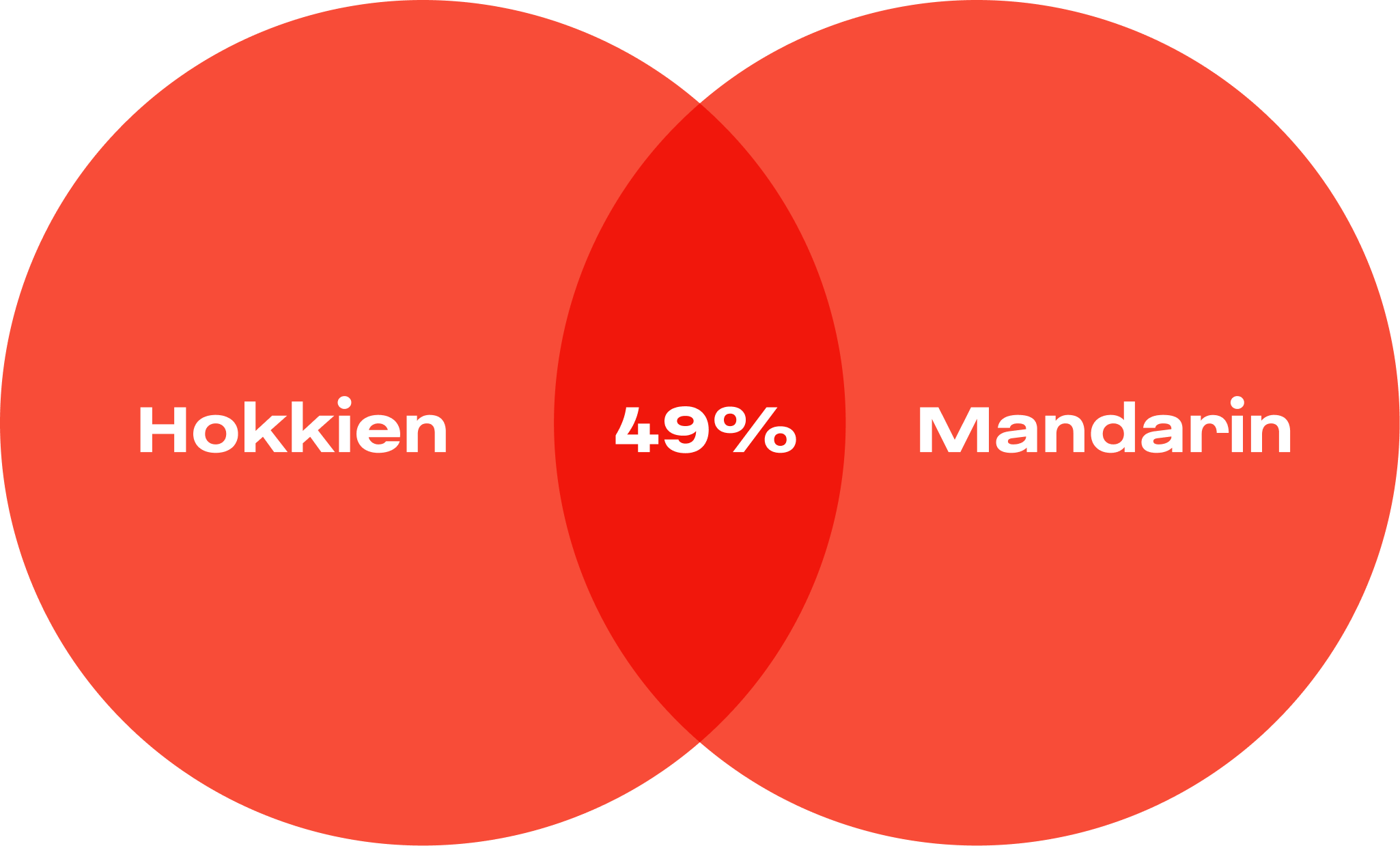

Hokkien shares only 49% of its basic vocabulary with Mandarin.

This may sound high, but to put this in context, English shares 59% of its basic vocabulary with German, 10 percentage points more than Hokkien and Mandarin.³

Chapter 03

The Formal

Written Language

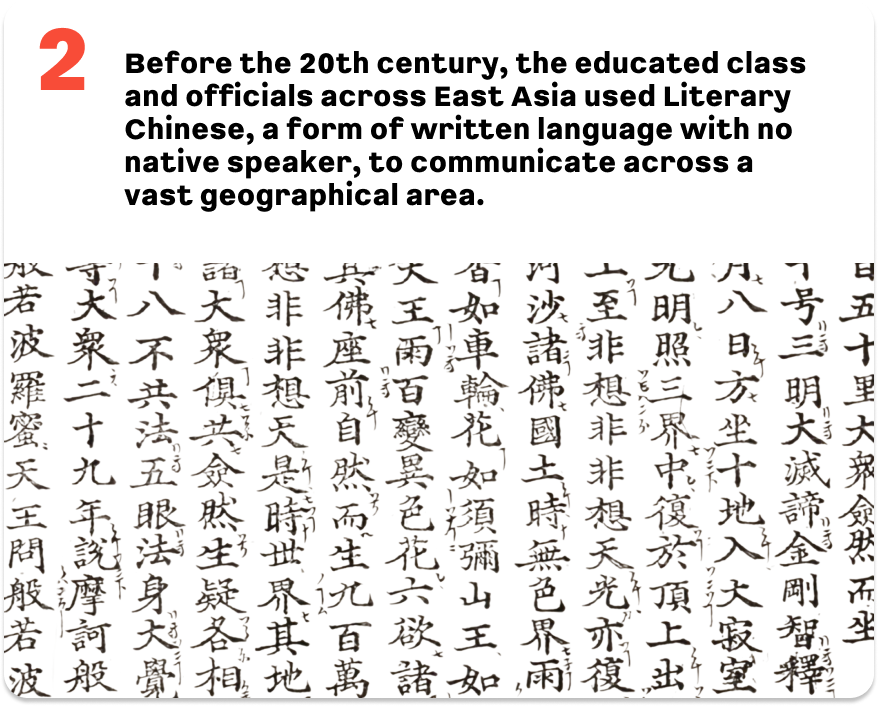

Despite the diversity of the spoken languages, the educated class and officials in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam used a form of written language that nobody spoke as a vernacular (everyday) language for nearly two millennia, known as Literary Chinese 文言. It is believed to be based on a spoken language in the Central Plain of China from the late 6th to the early 2nd century BCE.

This written language gradually spread to other parts of China and East Asia serving as a shared language of government and scholarship, and acted very much like Latin in Europe, and Sanskrit in South Asia.

Literary Chinese was gradually abandoned in the first half of the 20th century because it was seen as difficult to learn.

The characters and grammar in major classical period works, such as Analects of Confucius 論語, Records of the Grand Historian 史記, Mencius 孟子 and Commentary of Tsó (Zuo) 左傳, became the prototype upon which later writers modelled their work.

The educated elites were trained to write the classical language through mechanical memorisation. The exact sounds represented by the characters in the classical texts are not fully understood.

But every region in East Asia has its own pronunciation where the vocalisation is dictated by many factors including the original pronunciation, local language, evolution, influences from the neighbouring urban centres, capital cities and other languages it comes in contact with.

Use the arrows to see how different languages pronounce the same Literary Chinese 文言 sentence.

Hokkien

有朋自遠方來,不亦樂乎

Iú pêng tsū uán-hong lâi, put e̍k lo̍k hoo

To provide an analogy, the letter ‘j’ has different pronunciations in different European languages.

J

in English

/dʒ/

‘jar’

J

in German

/j/

‘ya’

J

in Spanish

/χ/

‘ha’

Did you know?

Hùn-tho̍k

訓讀

學而時習之、不亦悅乎

まなびて ときに これを ならう、また よろこばしからず や

(Manabite toki-ni kore-wo narau, mata yorokobashikarazu ya)

The 13th-century Ku-yeok In-wang-kyung 舊譯 仁王經 is a Literary Chinese text annotated by Korean speakers to help the interpretation of the text.

There were similar practices in Europe. Latin texts were annotated in languages of ordinary people (Old English, Old French, Old High German, Old Irish and many others) throughout the High Middle Ages. The main purpose of these annotations was to help the reader correctly interpret the base text using their native language. The 9th-century Vespasian Psalter kept at the British Library is an example.

Myth-buster

The bilingual (or diglossic) phenomenon of the educated class across east Asia being able to read and write Literary Chinese, a shared written language, fuelled the myth that all Chinese languages share the same written form.

People often claim the first emperor of Tsîn (秦 Qin) to have unified the language of China two millennia ago to express their support of Mandarin replacing Hokkien and other languages. The fact is that the emperor did not standardise the spoken language but only the characters.

Chapter 04

Informal Writings

Across East Asia

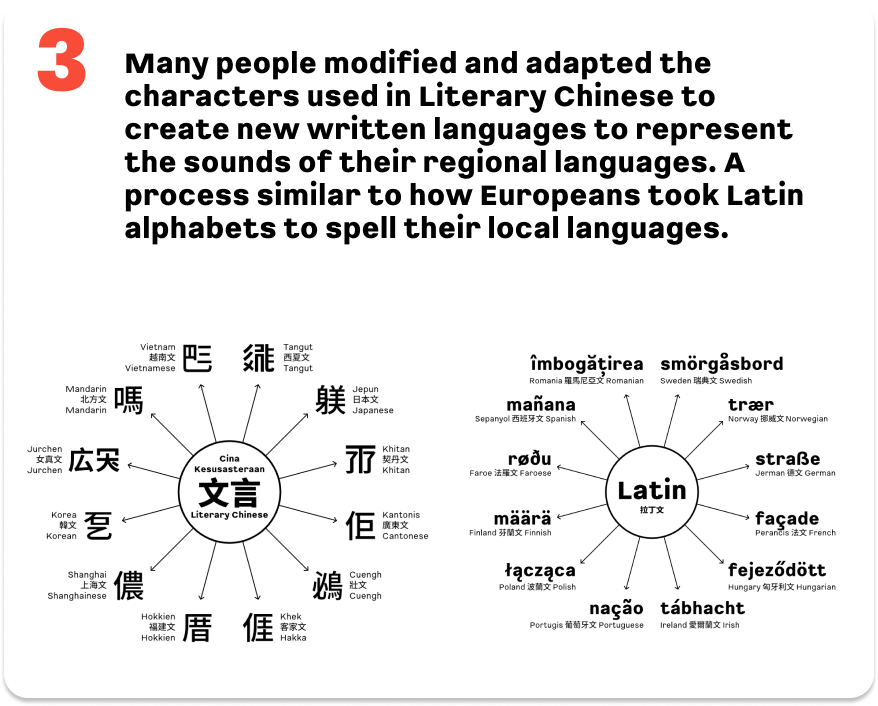

The characters in Literary Chinese provided a prestigious way of writing. Many people in East Asia used them as a starting point and adapted the characters to create new written forms to represent the sounds of their local languages.

Written Japanese

The Japanese created the Kana (仮名) script based on the simplification of the characters in Literary Chinese during the Heian period (794–1185). The classical language coexisted with native Japanese writings, similar to Europe where Latin coexisted with common European languages. This gives us a frame of reference for the situation in other parts of East Asia.

People in East Asia used characters in Literary Chinese as a starting point and adapted the characters to create new written forms to represent their local languages.

Written Vietnamese

In many other parts of East Asia, people derived their local languages by compounding and repurposing existing characters found in classical texts. From the 13th century onwards, the Vietnamese people started to write poems in the local language using locally invented compound characters known as Chữ Nôm.

Chữ Nôm

The development of Chữ Nôm was severely disrupted after the invasion of the Chinese army in 1407 but sustained a revival from the middle of the 17th century up until the Roman alphabets were enforced by the French colonial government in 1910.⁴

The Vietnamese people used characters in Literary Chinese to create compound characters known as Chữ Nôm to write Vietnamese.

Did you know?

Not all Chinese characters are pictographs

Not all Chinese characters are pictographs, to which readers may assign any pronunciation to any character (or pronounce however they like). In fact, the majority of Chinese-based characters are compound characters, usually formed by a part that represents the meaning (semantic), and the other part that represents the sound (phonetic). Most readers can make an approximation of how a character is pronounced based on the phonetic part of the characters.

Myth-buster

The popular belief that all Chinese characters are mere symbols resembling physical objects or representing ideas is just a myth. In fact, such characters make up only a minority as it is difficult to represent abstract concepts by creating symbols. Most Chinese characters have a phonetic component.

The belief that Chinese characters are mere logos, where readers can arbitrarily assign any sound to them also helps reinforce the myth that all Chinese languages share the same written form.

Written Mandarin

In the centuries that followed, Mandarin was increasingly used in other genres of literature. Novels such as Water Margin 水滸傳 and Dream of the Red Chamber 紅樓夢 are examples of literature rendered in part-Mandarin and part-classical writings.

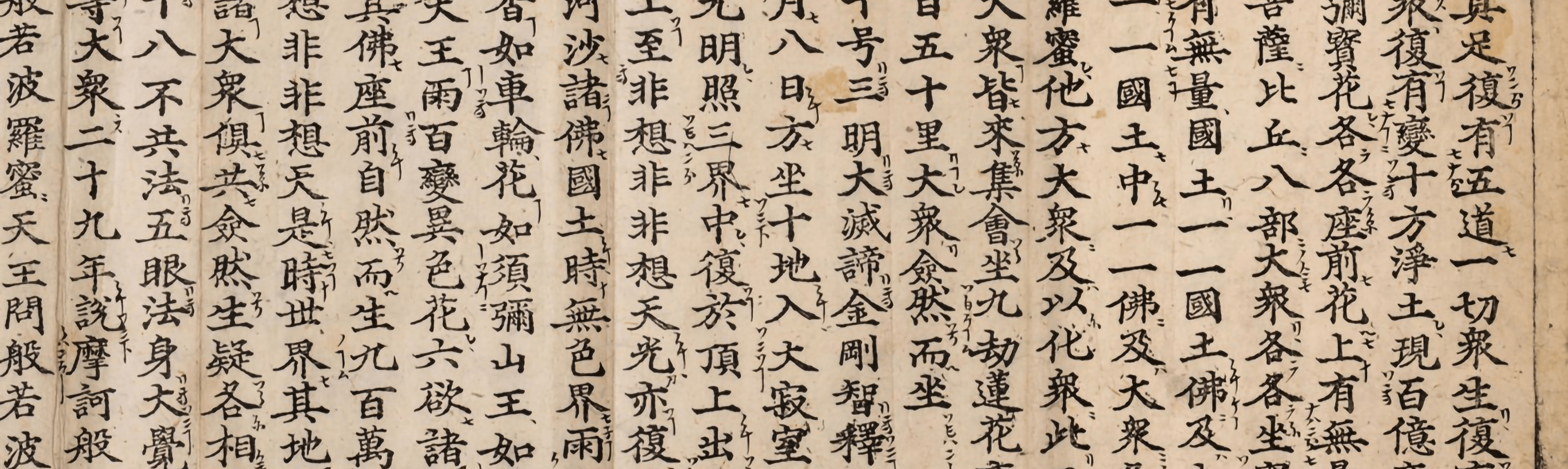

The earliest traces of Mandarin can be found in 10th-century Buddhist scriptures.

The Buddhist scriptures are known as ‘Transformation Texts’ 變文 and ‘Sutra Explanations’ 講經文 discovered in Tun-hông (敦煌 Dunhuang). Texts with a stronger influence of written Mandarin can be found in another genre of literature popular amongst the neo-Confucian scholars known as ‘Records of Words’ 語錄.

However, Mandarin is not the only language in China that developed a written form. Many other languages such as Hokkien, Cantonese, and Shanghainese also developed their written languages.

Even much smaller languages such as the various languages of the Cuengh 壯, Pe̍eh (白 Bai), Kam, Biâu (苗 Miao), Iâu (瑤 Yao) have developed written traditions in a similar fashion.

This is the Cuengh language.

It was only in 1920 that Mandarin replaced Literary Chinese as the official written language. Other written Chinese languages were not given any official status even in their respective regions and worse, were labelled as ‘dialects’. The reasons for that will be explained later.

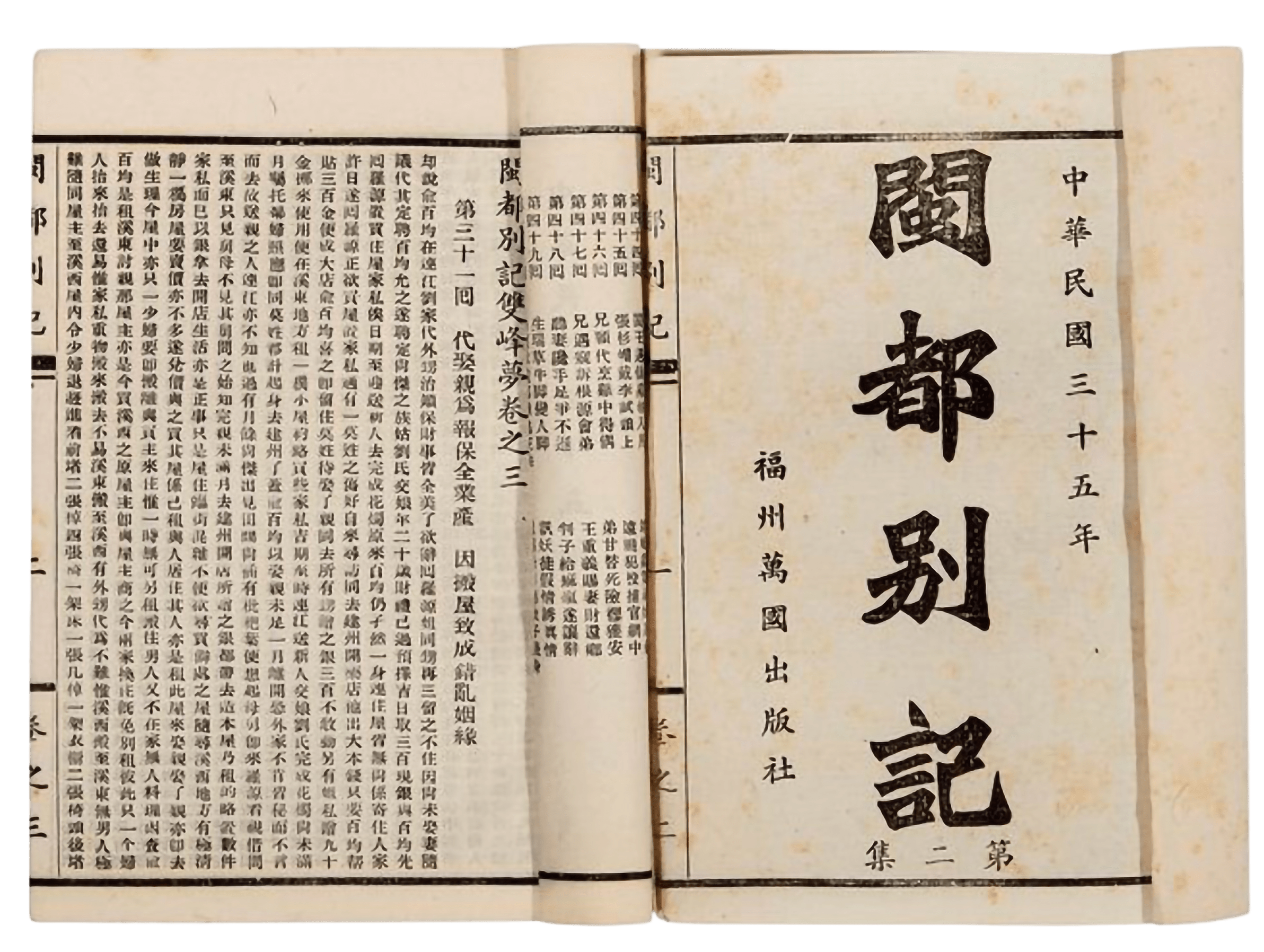

Written Hokkien and Teochew

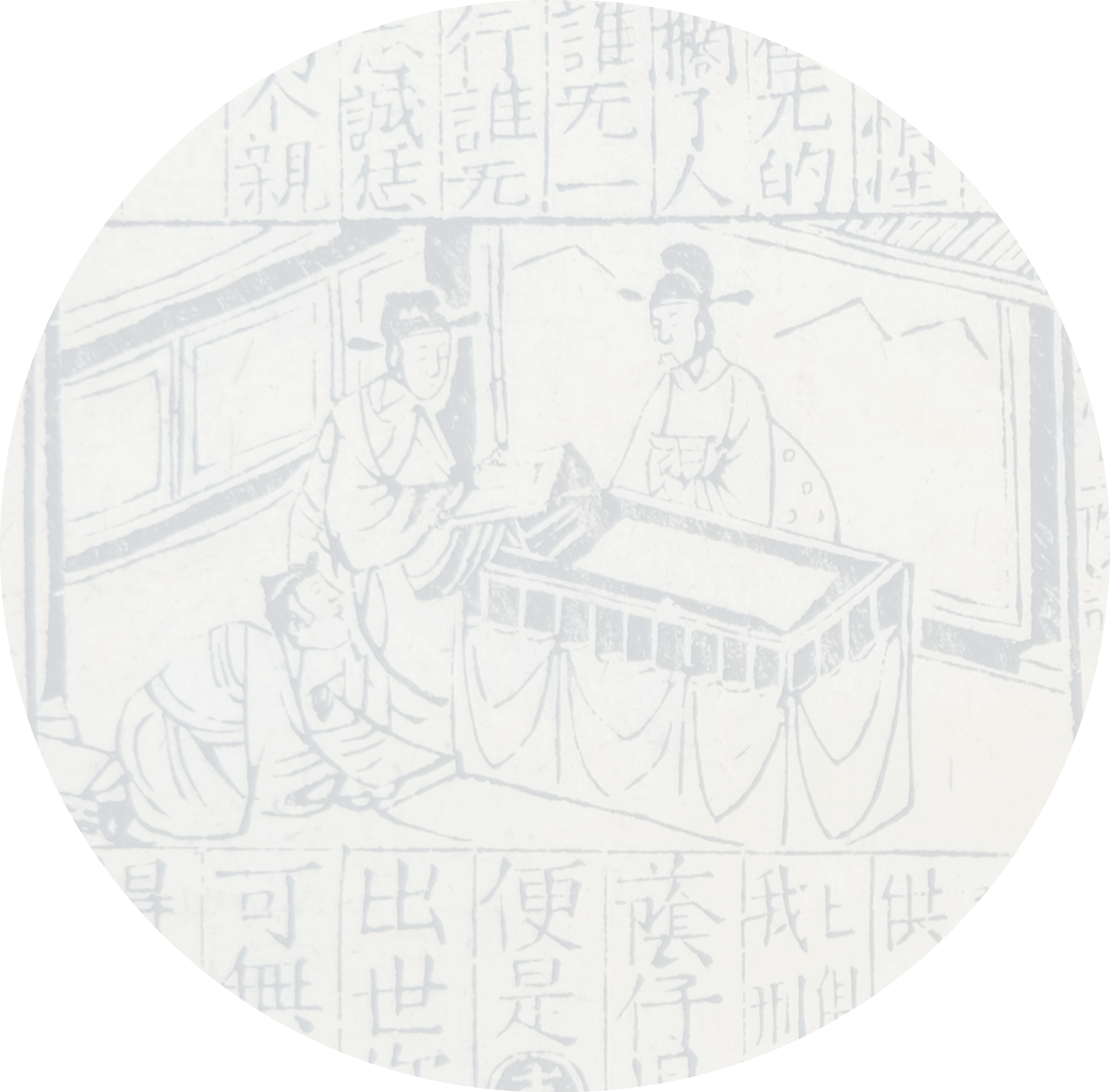

The oldest surviving book that has a significant amount of written Hokkien and Teochew is a theatre playbook entitled Tale of the Lychee Mirror 荔鏡記 or more commonly known as Tân-sann Gōo-niôo 陳三五娘. The version that survives to this day is the version reprinted in 1566, which implies that the first publication of this book was dated even earlier.

Tale of the Lychee Mirror

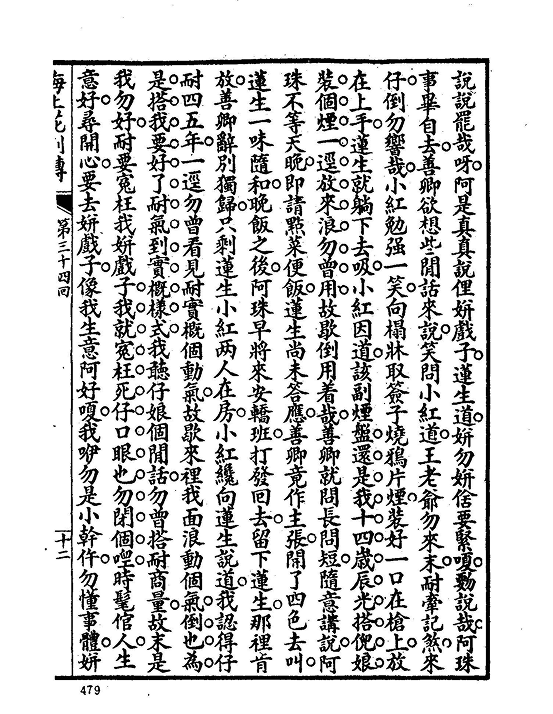

Another popular genre widely

written in Hokkien and Teochew is

a type of poetry chapbook known

as ‘Kua-á-tsheh’ 歌仔冊 in Hokkien

or ‘Kua-tsheh’ 歌册 in Teochew.

An example of the Hokkien poetry chapbooks known as ‘Kua-á-tsheh’.

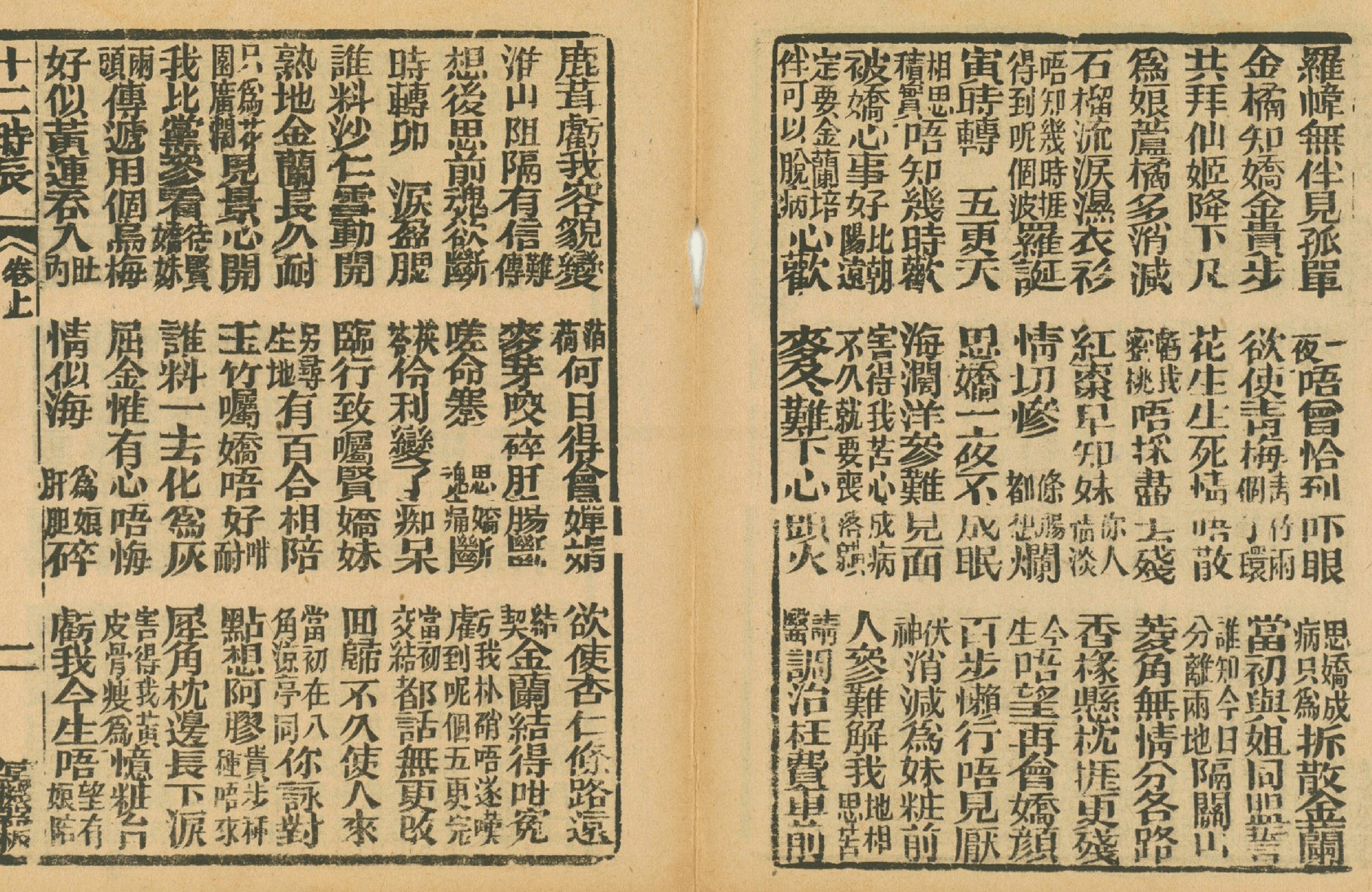

Other Written Languages in the South

Special Stories of the Hokchew City 閩都別記 is a notable 400-chapter novel written in Hokchew.

The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai 海上花列傳 is a famous novel written in Shanghainese whereas a genre of songbooks known as ‘strum lyrics’ 彈詞 popular in Soo-tsiu (蘇州 Suzhou) has a rich record of the Gôo 吳 language.

A genre of Cantonese songbooks known as ‘Wooden Fish Books’ 木魚書 was widely popular in the Cantonese speaking region whereas Hakka writings can be found in ‘Mountain Songbooks’ 山歌書.

An example of the Cantonese ‘Wooden Fish Books’.

This literature was hugely popular, but due to the lack of prestige, many of them were not well-preserved, and the majority became lost.

Apart from novels and poems, regional languages were also commonly used in religious texts 科儀書, contracts and printed materials and many other non-official texts.

Publications in the Roman Script

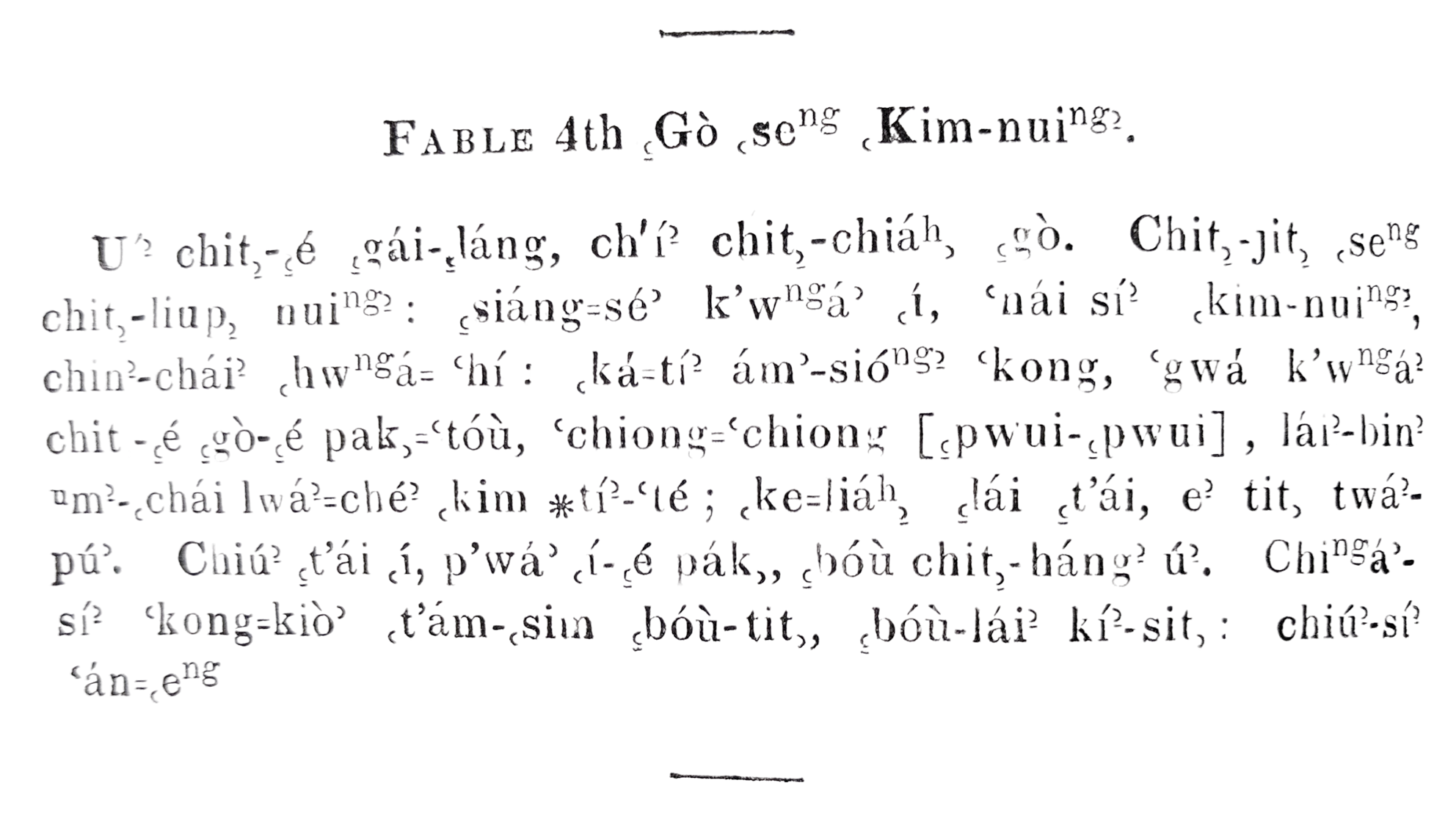

The arrival of Western missionaries in the east, particularly in the 19th century, led to an explosion of vernacular (spoken) Chinese languages written in the Roman alphabet.

Samuel Dyer

Samuel Dyer from the London Missionary Society, who lived in Penang for eight years, translated Aesop’s Fables into Romanised Hokkien and published his book in Singapore in 1843. The spelling system he employed continued to evolve and later became known as Pe̍h-ōe-jī 白話字.

The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs story in Dyer’s Aesop’s Fables (1843).

The Romanised Hokkien (Pe̍h-ōe-jī 白話字) became very popular. At its peak, it is estimated that one in three letters posted in the Hokkien-speaking region of China were written in Pe̍h-ōe-jī. Even the postal service had no problem delivering letters to addresses written in the romanised Hokkien.⁵

In 2006, the Taiwanese government improvised and standardised Pe̍h-ōe-jī to cover major accental differences and renamed it as Tâi-lô 台羅.

The Principles and Practice of Nursing by

George Gushue-Taylor (1917)

The Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew’s political speech was written in Pe̍h-ōe-jī when he was campaigning in Singapore’s 1963 general election.

Periodical Publications in Southern Chinese

By the end of the 19th century, the press started to produce newspapers and magazines in different Chinese languages. The first Mandarin newspaper, The Peoples’ Newspaper 民報, was published in 1873. Languages in southern China also had their printed periodicals too.

The Voice of Teochew 潮聲 is a newspaper written in Teochew published in 1906.

The Vernacular Newspaper of Canton 廣東白話報 (1907) and The Vernacular Magazine of Leng Naam 嶺南白話雜誌 (1908) were published in the Cantonese language.

Due to its prestige, nearly all works written in regional languages invariably exhibit the influences of the classical writings. It is often difficult to categorise a work as vernacular (ordinary language) or literary as the literature forms a long spectrum of styles and registers. Generally speaking, the more formal a work is, the greater it resembles the literary language.

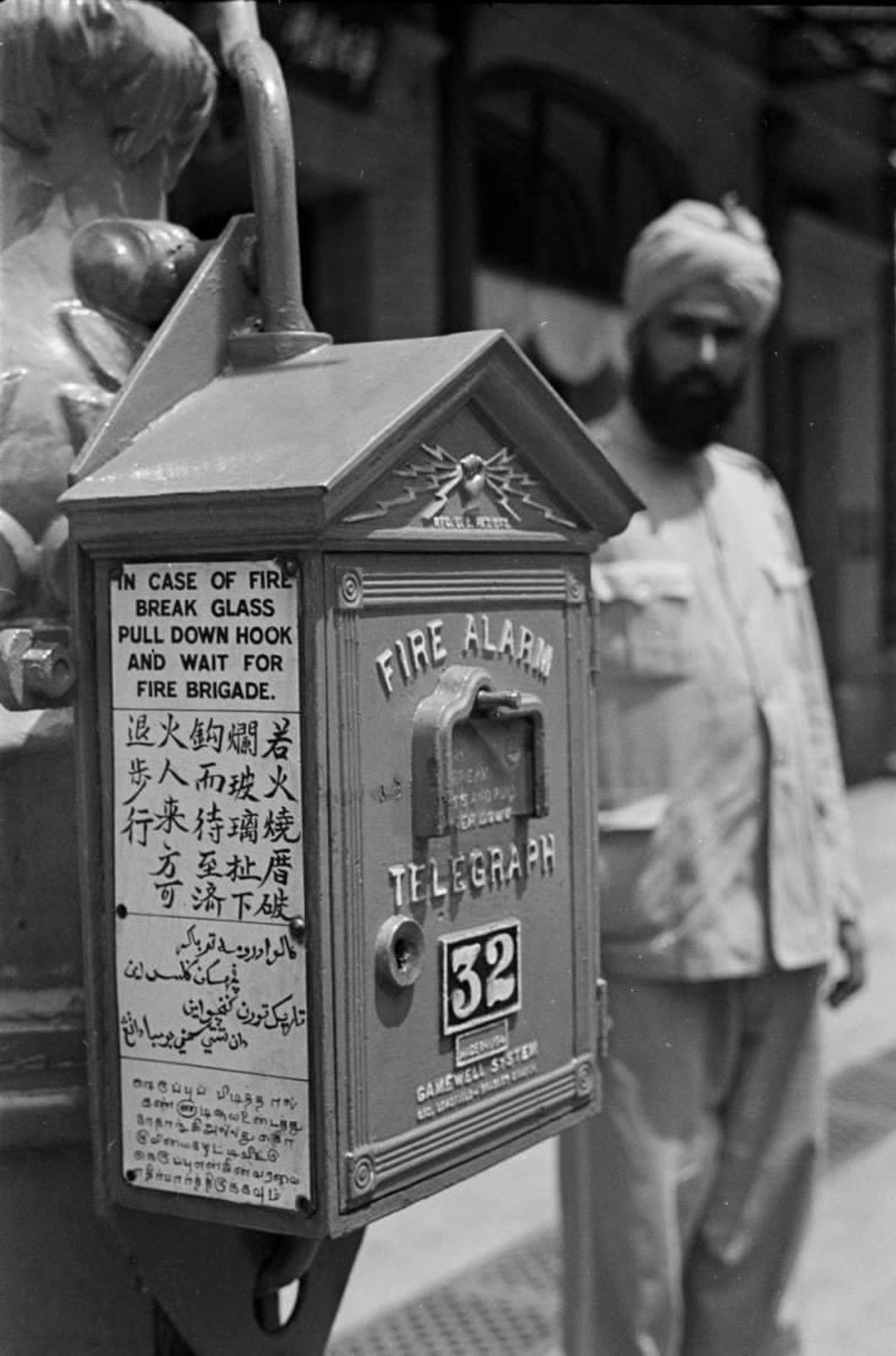

A fire alarm instruction in four languages – English, Literary Chinese with a recognisable Hokkien phrase ‘hué sio tshù’ (火燒厝), Malay in Jawi script and Tamil. (Photo by Harrison Forman in Singapore, 1941)

The written forms of southern Chinese languages developed in a similar fashion to Mandarin. But their development was restricted and uses were curtailed in the 20th century due to the change in the belief system of their speakers about their languages and identities.

Chapter 05

Hokkien in Full Use

Before the 20th century, each region had its own customs and traditions and enjoyed high cultural autonomy. Local languages were used in all aspects of the lives of the local population.

“It (Hokkien) is not a mere colloquial dialect or patois; it is spoken by the highest ranks just as by the common people; by the most learned just as by the ignorant”

– Carstairs Douglas, Missionary of the Presbyterian Church in England (1873)

An early 18th-century pronunciation dictionary, Tōo-kang-su Si̍p-ngóo-im 渡江書十五音.

Schools were teaching in their local languages too, and teaching materials were developed to transmit the local pronunciation of Chinese characters. Several notable pronunciation dictionaries, commonly known as ‘Fifteen Sounds’ 十五音, were widely available in the Hokkien and Teochew region. Most educated people learned the local pronunciations of Chinese characters through these dictionaries.

In southern China (non-Mandarin regions), only a small group of government officials could communicate in Mandarin. This was generally the case up until the 20th century.

Mandarin was the spoken language of the imperial court centred in the north. This is how the northern variety of Chinese derived its name.

‘Mandarin’ 官話 literally means ‘the language of the officials’. This English word entered the English language as a loanword from the Portuguese ‘mandarim’ in the 16th century. This word is believed to have two influences: the Sanskrit term ‘mantri’ (मन्त्रि minister) and the Portuguese verb ‘mandar’ (to command).⁶

Local dialects differ from town to town and the varieties spoken in large urban centres often serve as the standard in their respective region.

The Amoy dialect is the lingua franca of the Hokkien speaking region; the Canton dialect is the lingua franca of Kuínn-tang (廣東 Guangdong) and some parts of Kuínn-sai (廣西 Guangxi). Shanghainese is widely accepted as the standard of the northern Gôo (吳 Wu) region.

Different Peoples,

Separate Languages

Before the 20th century, people in China did not see their languages as a single language. The view that Chinese is a single language with many dialects only emerged after the rise of Hàn nationalism at the end of the 19th century.

The 18th-century Tsheng (清 Qing) government had already acknowledged how the languages in Kuínn-tang (廣東 Guangdong) were incomprehensible to each other. The description of the distribution of Hakka, Cantonese and Teochew in the province are in line with the linguistic taxonomy of the present day.

“The language in Heng-lêng (興寧 Xingning) and Tióng-lo̍k (長樂 Changle) is similar to Siau-tsiu (韶州 Shaozhou). The word for ‘I’ is ‘ngaai’. The Cantonese people call them ‘Ngaai4 zi2’. Teochew is spoken in the east and is similar to Hokkien. Teochew has many words that do not have written forms and is incomprehensible to the Cantonese. The language in Tiāu-khèng (肇慶 Zhaoqing), Ko-tsiu (高州 Gaozhou), Liâm-tsiu (廉州 Lianzhou) and Luî-tsiu (雷州 Leizhou) are similar to Cantonese but the people there can’t express themselves well. In Cantonese, the measure word is ‘go3’ 個 for humans and ‘zek3’ 隻 for animals, but it is the other way round in the aforementioned regions. The Hái-lâm (海南 Hainan) island is out in the sea. Their language is similar to the Teochews and they sometimes sound like the Hokkiens. Some people amongst them speak like the people in Liâm-tsiu 廉州.”

— Comprehensive Records of the Kuínn-tang (廣東 Guangdong)(1731)

The Comprehensive Records of Kuínn-tang (Guangdong) amended in 1561 described that Cantonese is the ‘proper’ language and Teochew sounds ‘foreign’. This is how people of different linguistic groups thought of each other’s language…

“The Hakkas are still speaking their own language even though they have been living and working as labourers in Tseng-siânn 增城 for generations. Their language sounds like bad noise. Without even asking them you can tell they are not from this place.”

— The Records of Tseng-siânn 增城 County (Khiân-liông 乾隆 period)

“Teochew sounds like a foreign language. It is very similar to Hokkien and therefore there are many words which do not have written forms. It is also not mutually intelligible with the languages in the surrounding regions.”

— The Comprehensive Records of Teochew 潮州府志 (Khiân-liông 乾隆 period, 1762)

Tionn-kû 張渠, a Mandarin speaker from Hô-pak (河北 Hebei) living in Huī-tsiu (惠州 Huizhou) in 1730, a town populated with Cantonese, Hakka and Hoklo (Swabue-Teochew) people, described the languages in the region as “incomprehensible like foreign languages” (侏㒧難解).

“The barbaric Kuínn-tang (廣東 Guangdong) and Hok-kiàn (福建 Fujian) provinces are inhabited by the descendants of the Five Emperors. These inhabitants keep genealogical records of their families. Their customs are similar to the Nine Provinces (China). How can they be the same as those barbarians from the desert who usurped our emperors with their shields and axes?”

— Tsiong Péng-lîn 章炳麟, Book of Coercion 訄書 (1899)

That Tsiong Péng-lîn needed to justify how people in Kuínn-tang (Guangdong) and Hok-kiàn (Fujian) provinces were similar to other provinces, is itself evidence of how people in different parts of China did not see themselves as one people.

Chapter 06

Who Counts as

‘Ethnic Hàn’?

Over 90% of the Chinese people identify themselves ethnically as ‘Hàn’ 漢 today. But the term ‘Hàn’ was not an ethnic group before the 20th century. It was a category used by people from outside China such as the nomadic people in the north to refer to the sedentary population who engaged in agriculture. It had a similar connotation as the word ‘Malaysian’ does today, in that it did not refer to any particular ethnicity.

The people who would consider themselves as ‘ethnic Hàn’ or ‘Chinese’ today saw each other as different people in the past.

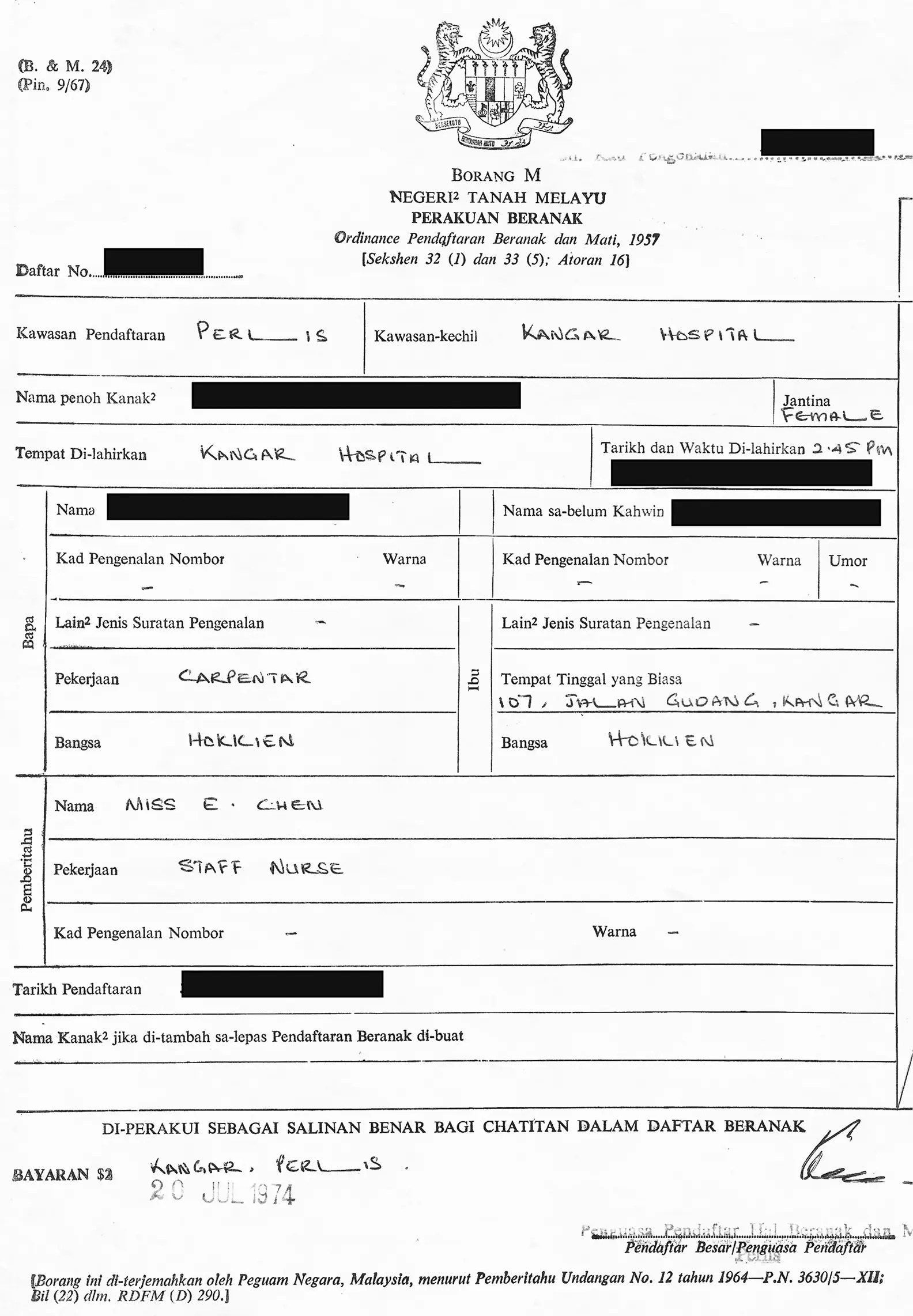

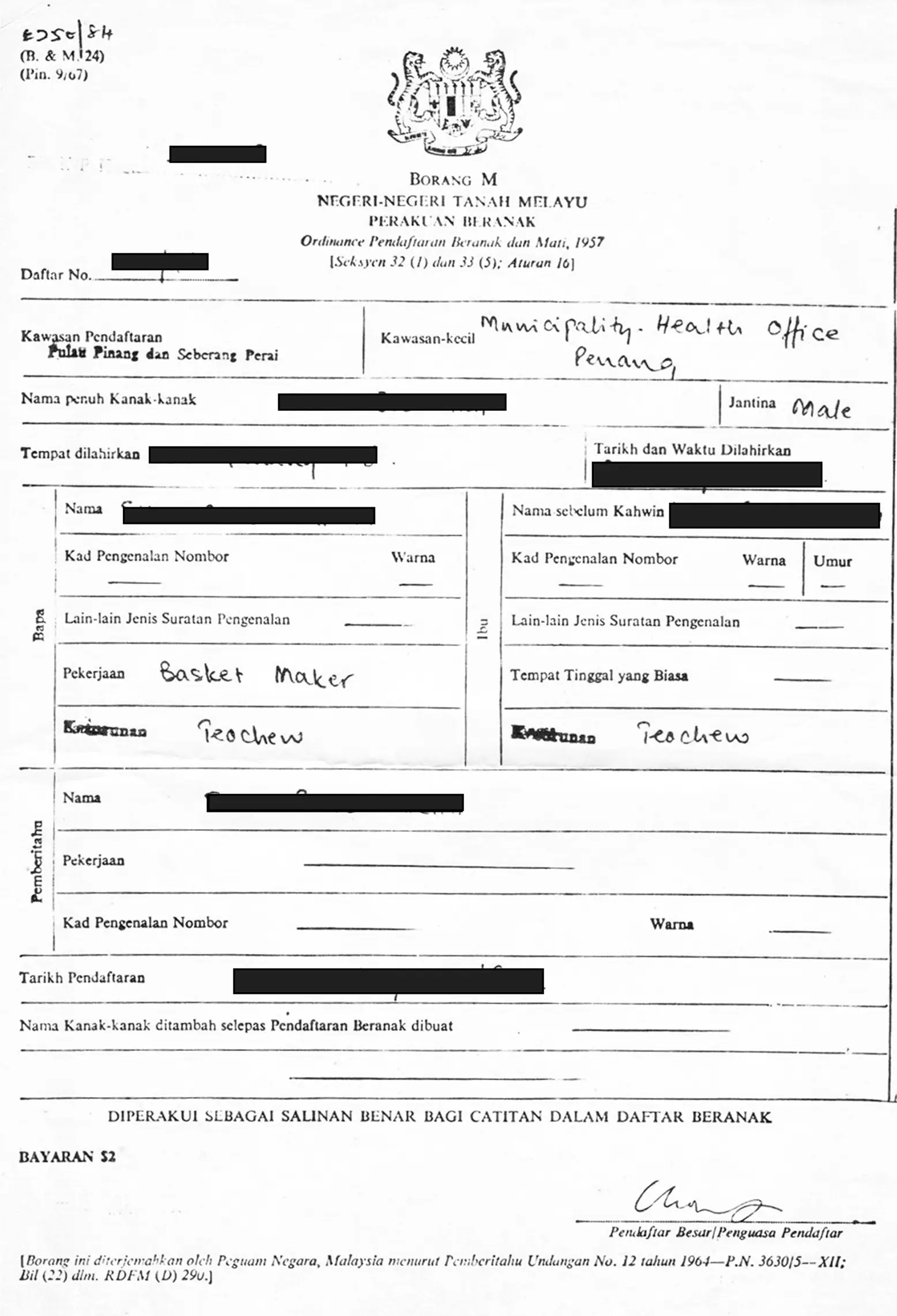

This can still be seen from the Malaysian national registration system, particularly in the first half of the 20th century.

Many Chinese Malaysians did not identify themselves as ‘Chinese’ but rather by their respective linguistic group, such as Hokkien, Hakka, Cantonese, Teochew etc.

Malaysia’s birth certificates separated the Hokkiens and the Teochews as two different ethnic groups.

The Hokkiens (Sangleys) and the Hakkas were depicted as separate ethnic groups in a 16th-century manuscript known as the Boxer Codex.

The depictions of the Hokkiens and Hakkas in the Boxer Codex.

The Vietnam government also classes the indigenous Hakka and Cantonese-speaking populations living in villages across the Vietnamese border as different people–the Ngái and Sán Dìu. They are not considered as ‘Hàn’.

The image above taken in the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology, Hanoi, showing photographs of people from different ethnic groups.

The Sán Dìu and Ngái are both Cantonese and Hakka speakers living in northern Vietnam. The Hoa (centre, top) has been created based on ethnic ‘Hàn’ ideology to include the descendants of all Chinese immigrants living in major cities, which also includes Cantonese and Hakkas, despite Cantonese and Hakka speakers already being represented.

This display highlights how arbitrary ethnic categorisation can be.

Who Were the ‘Hàn’ in Historical Records?

The term ‘Hàn people’ 漢人 can be found in the historical records but it was mainly used to refer to the people under the rule of the Hàn dynasties two millennia ago; Western Hàn (202BCE–CE23) and Eastern Hàn (25–220). This was therefore a political term, not an ethnic one, and fell out of use after the dynasties collapsed.

It was not until the Mongol rule (1271–1368) that the word ‘Hàn’ was used again. The Mongols divided the population into four groups; Mongols, Sek-bo̍k 色目, Hàn 漢 and Southerners 南人. Southern Chinese people who think of themselves as Hàn today were not considered by the Mongols as Hàn but as Southerners 南人. Contrarily, some Khitan and Jurchen people living in certain areas were classified as ‘Hàn people’ 漢人.

The term ‘ethnic Hàn’ 漢族 only occurs rarely in historical texts before the end of the 19th century and did not carry the modern meaning of Hàn ethnicity. For example, it was used to refer to a Korean person by another Korean, and it was the last known use of the term.⁷

China was a kinship-based society and did not have the modern idea of a ‘nation’. This began to change at the turn of the 20th century when the concept was imported from the West through Japan, and when identity politics was used as a weapon to overthrow the rulers.

China did not have a word for ‘nation’ or ‘ethnicity’. The modern word ‘bîn-tso̍k 民族’, is a Japanese-invented word borrowed into Chinese.

The most common terminology used by the southern Chinese to refer to themselves is Tn̂g-suann-lâng 唐山人 (or Tn̂g-lâng 唐人) which means ‘people of the Tn̂g mountain’. Again, this is a geographical term and not a bloodline kinship term.

Chapter 07

How the ‘Ethnic

Hàn’ Was Created?

Element 1

External

Threat

From the mid 19th century, the encroachment of foreign powers became a growing concern to the Chinese elites. In 1895, China lost a war to Japan, and such a defeat by a former tributary state was a bitter psychological blow. In order to modernise their country, many students went to Japan and to the West to study.

One of the ideas they brought back was the western classification of humans into races and many people took the idea as scientific truth.

Element 2

Social Darwinism

& Racism

In December 1897, Giâm Ho̍k 嚴復 translated Thomas Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics 天演論 into Literary Chinese. A modified Darwinian idea of natural selection originally applied on different biological species was used on one species, human beings. This idea, known as Social Darwinism, started to spread in China.

“Evolution and Ethics” by Thomas Huxley and its Literary Chinese translation.

Many who read his translation conceived the idea that all Chinese people belong to the ‘yellow race’, and that the ‘yellow race’ was competing with the ‘white race’.

The failure of the Hundred Days’ Reform in 1898 made many activists frustrated that the Manchu rulers hadn’t implemented reforms quick enough, and the group split into two camps; the reformists who wanted to continue to push for peaceful reform, and the revolutionaries wanted to overthrow the Manchu rulers altogether.

However, to the revolutionary camp, the ‘yellow race’ idea was no longer useful to mobilise the population, because the Manchu were considered to be included in this classification. They needed a new identity. The revolutionaries began reconstructing the ‘Hàn ethnicity’ to separate the Manchus from the ‘yellow race’ and in doing so they could convincingly galvanise hatred against the Manchu rulers.⁸

Element 3

Creating a Common Ancestor

In May 1899, a leader of the revolutionary camp Tsiong Péng-lîn (章炳麟 Zhang Binglin) wrote the article ‘Guest Emperor’ 客帝 and started to alienate the Manchu rulers as a ‘barbarian’ race. He became the first person to coin the term ‘ethnic Hàn’ 漢族 in the modern sense and became pivotal in defining the ethnic Hàn identity.

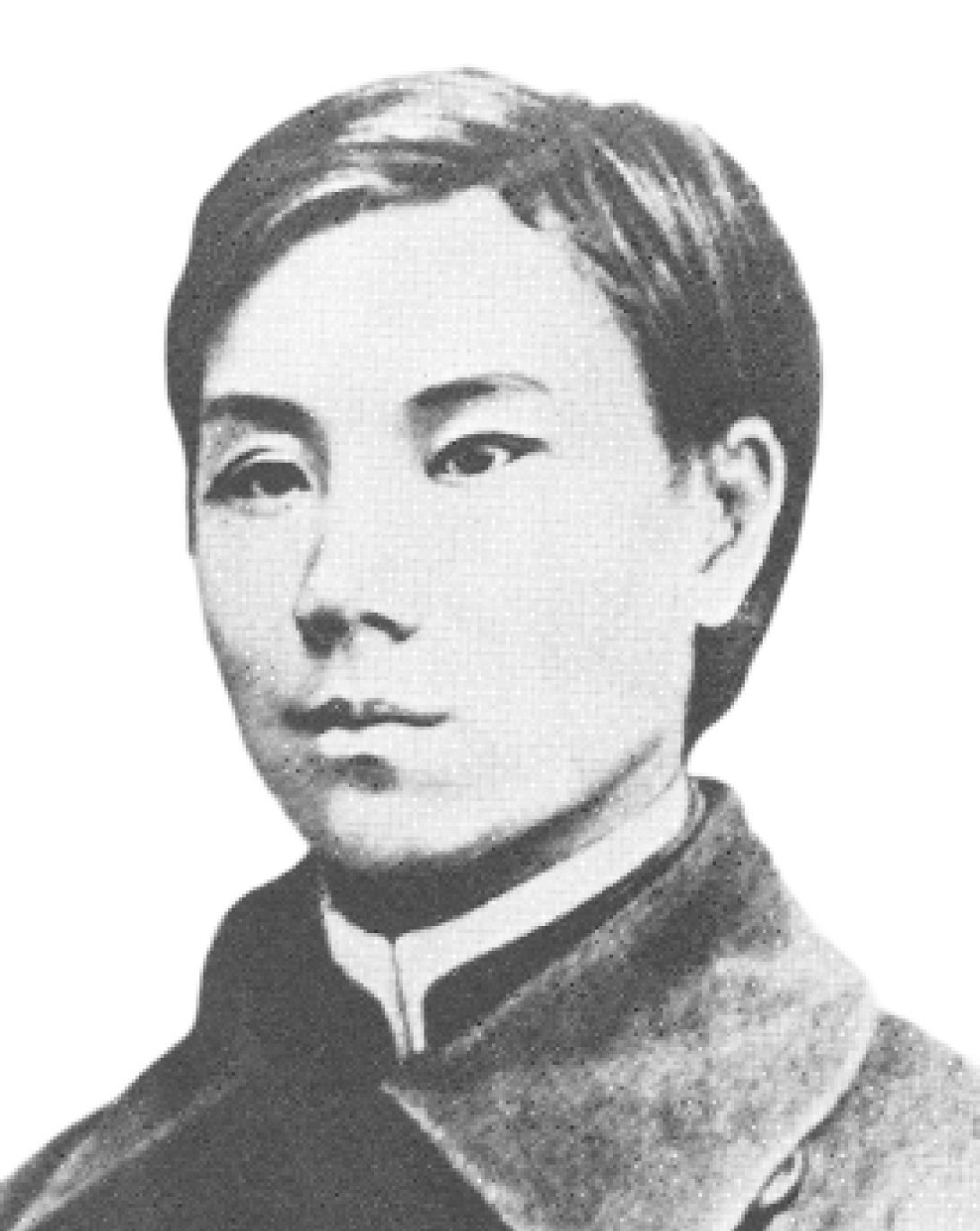

Tsiong

Péng-lîn

章炳麟

The revolutionaries described the Manchus as weak, corrupt and oppressive barbarians from the north who didn’t belong to China. They argued that the Manchu regime must be overthrown to save the people from being decimated by foreign powers.

They coined the word ‘racial extinction’ 滅種 as a way to stoke anxiety amongst the population by relying on the traditional fear of family extinction 滅族.

The ‘Hàn’ category used by the Manchu rulers to classify the population engaged in agriculture was convenient as a symbolic label for the new bloodline identity the revolutionaries were trying to invent.

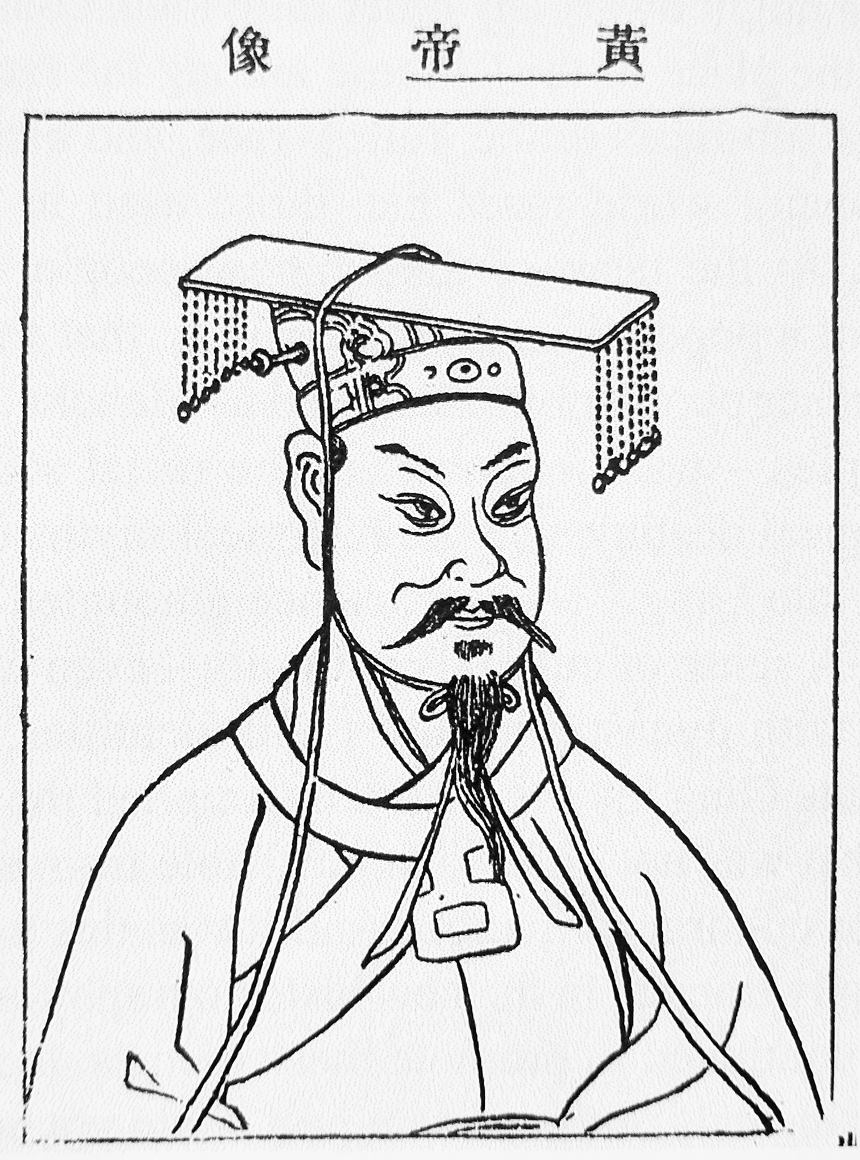

The educated class at that time were still aware of the mythical figure of the Yellow Emperor 黃帝 mentioned in Records of the Historian 史記 written by Su-má Tshian (司馬遷 Sima Qian). Even with no evidence that this figure ever existed, the revolutionaries made the Yellow Emperor 黃帝 the ancestor of all ‘ethnic Hàn’. By making such a claim, they had turned a diverse population into blood relatives, and this became a powerful political weapon to mobilise an uprising.

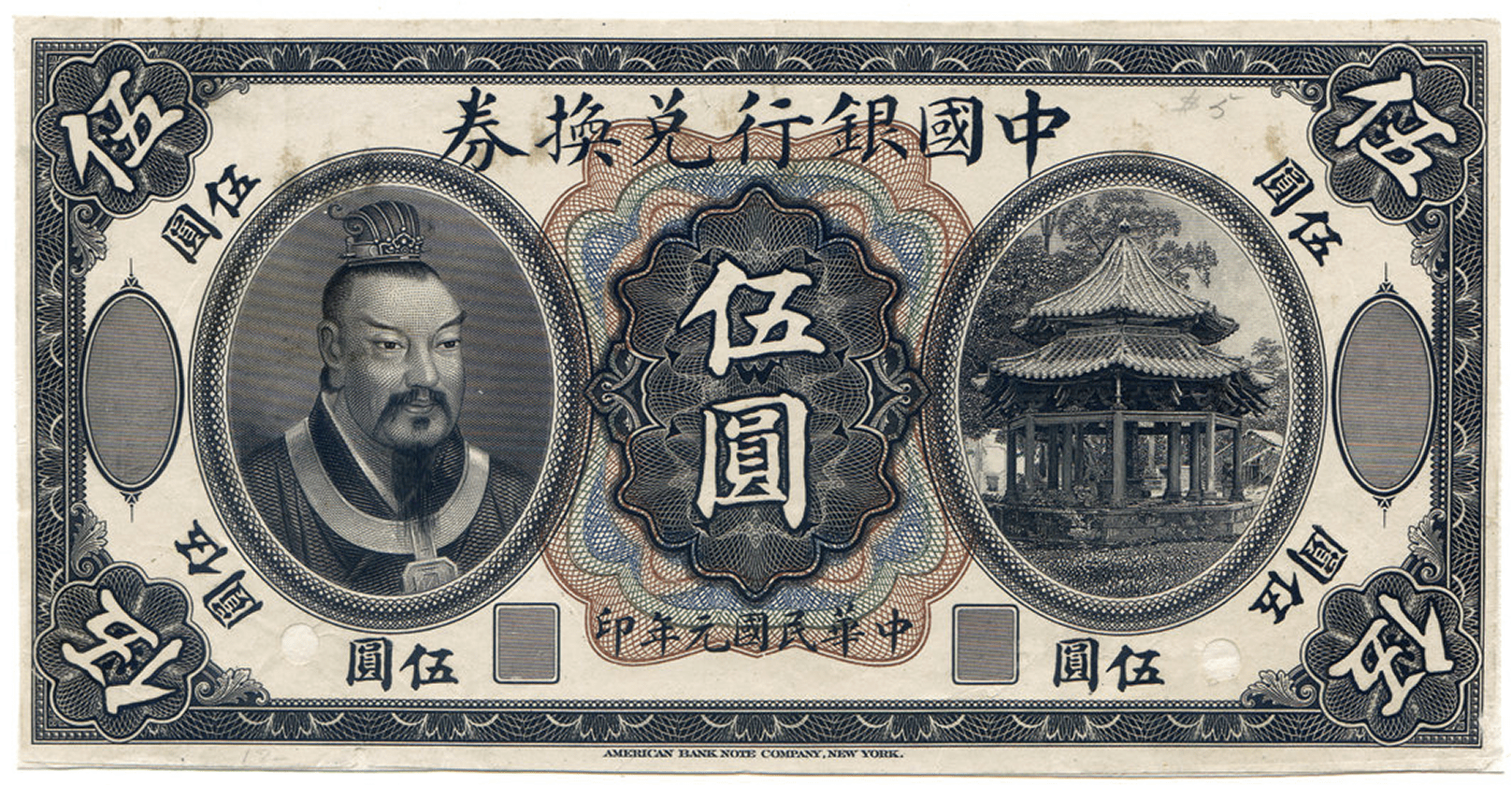

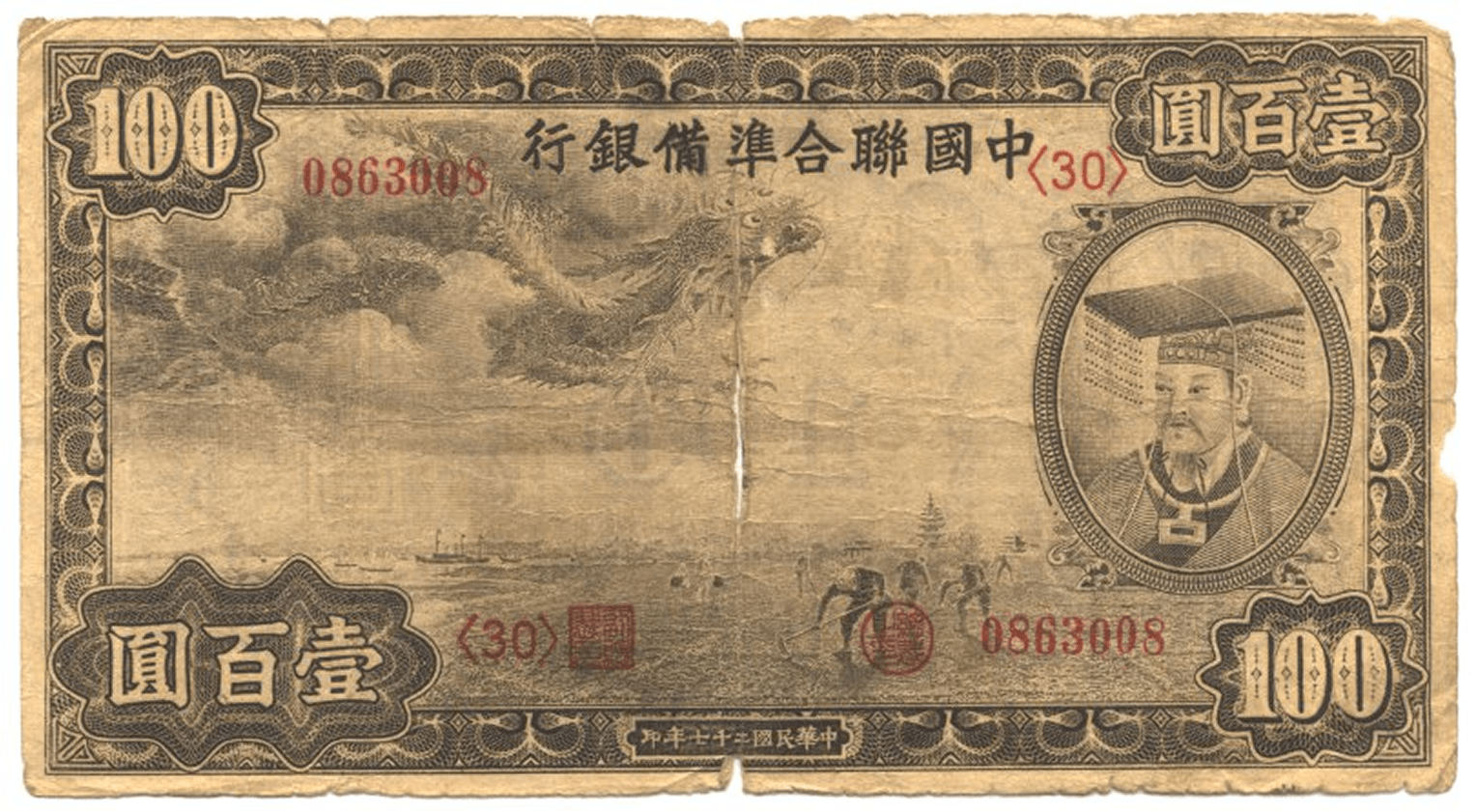

The Chinese nationalist government continued to promote the Yellow Emperor as the founding ancestor of the Chinese people. These depictions of the Yellow Emperor were found in early 20th-century textbooks and banknotes.

The Yellow Emperor was promoted as the founding ancestor of the Chinese people in school textbooks.

Banks also promoted the Yellow Emperor as the common ancestor of the Chinese people.

Anti-Manchuism

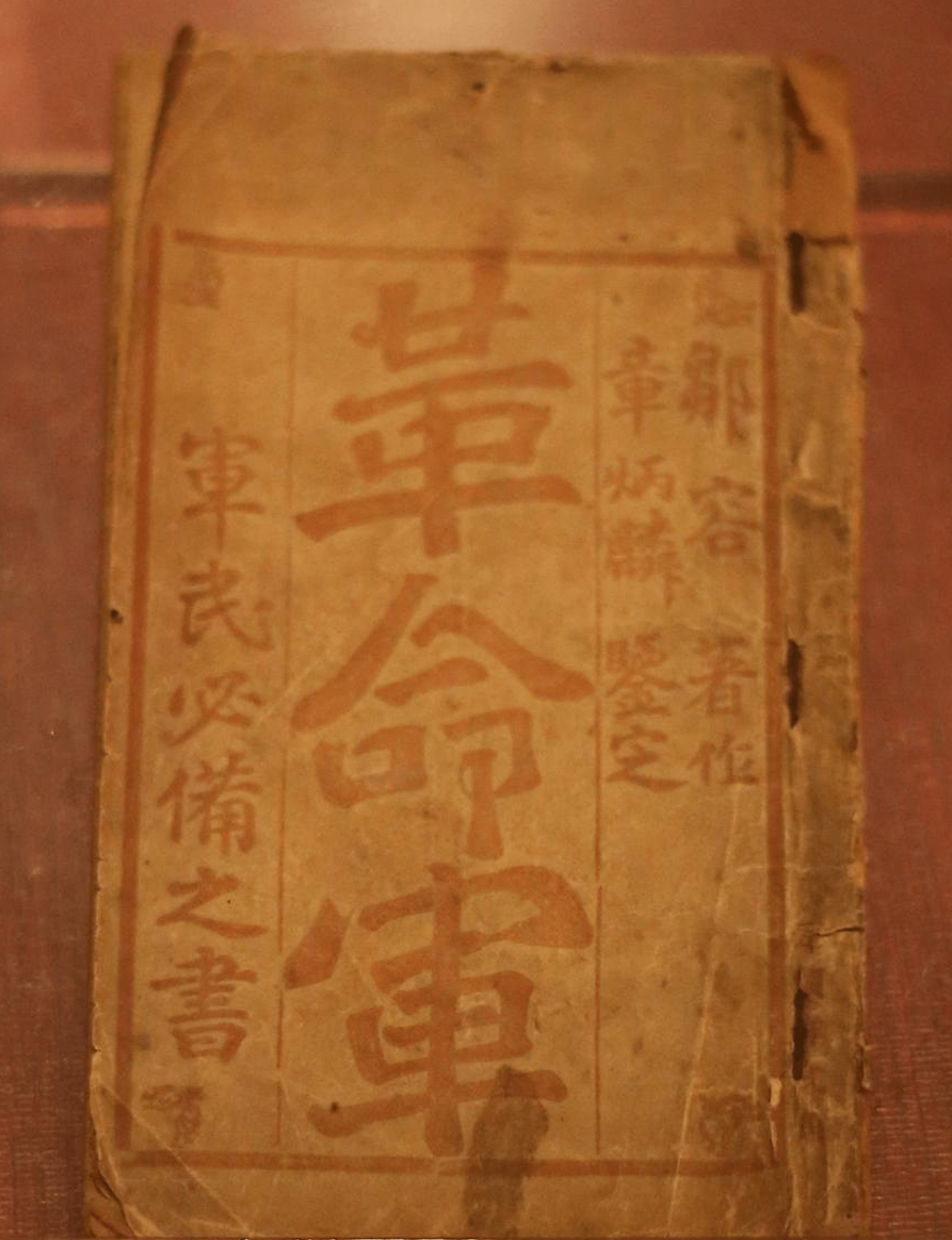

To alienate the Manchu, Tsau Iông (鄒容 Zou Rong) – who published the most influential revolutionary pamphlet The Revolutionary Army 革命軍 in 1903 – divided the ‘yellow race’ into sub-races.

Tsau

Iông

鄒容

The Revolutionary Army (1903)

According to his definition, the Chinese are of the Hàn ethnicity 漢族 and the Manchus are of the Tungus ethnicity 通古斯族 and he made it clear that “race must be clearly distinguished for a revolution to happen”.

In almost every chapter of his pamphlet, Tsau Iông (鄒容 Zou Rong) mentioned the mythological Yellow Emperor to ensure that the ‘candidate’ for the ancestor of the ethnic Hàn was reinforced in the minds of his audience.

Stoking Fear of External Threats to Stir up Hàn Nationalism

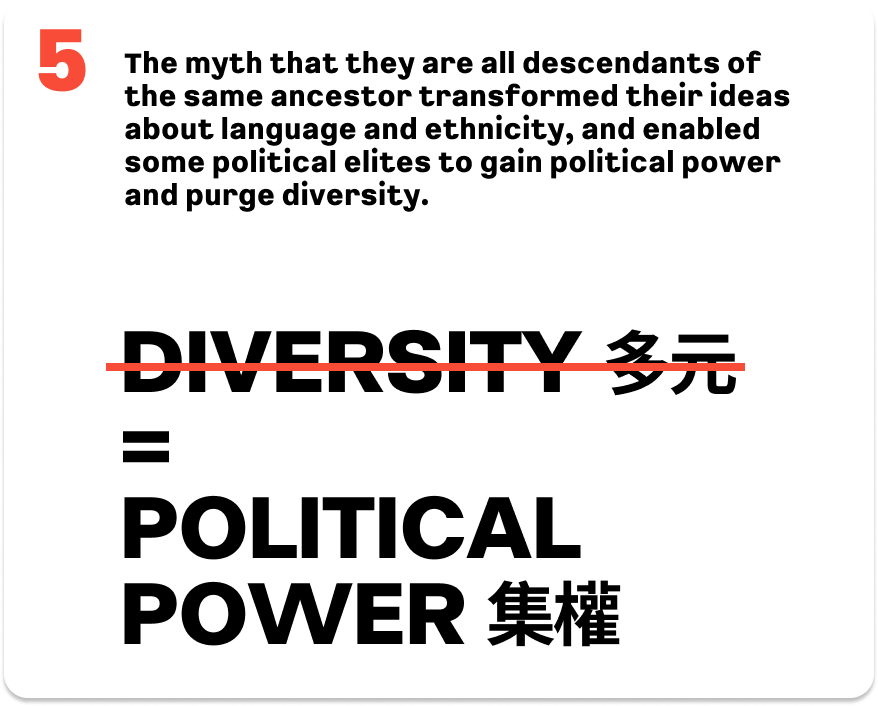

The definition of ‘Hàn’ encompassing a much wider population allowed the governing classes to centralise their power and rule over a larger population.

Although anti-Manchu sentiment quickly died down after the Manchu rulers were overthrown, ideas about racial competition and external threats still persist within the education system and political discourse. These ideologies continue to be used by the elites to garner support.

The promotion of Hàn nationalism has become a prelude for the domination of Mandarin, which forms the largest group within the Hàn group.

Chapter 08

The Minoritised

Majority

The dominance of Hokkien seafarers began in the 11th century. Má-huan 馬歡, a famous voyager, had reported the presence of the Hokkien people in Java as early as the 15th century. As a result of migration, many southern Chinese languages, particularly Hokkien, became the lingua franca in cities and towns in Taiwan and Southeast Asia.

With a high number of speakers, Hokkien emerged as a language for interlinguistic group communication. The prevalence of Hokkien can be observed in urban areas along the west coast of the Malay peninsula, particularly in Penang, Melaka and Singapore.

The development of Hokkien was curtailed by the rise of Hàn nationalism in the 20th century. When the Hokkien leaders began to consider other linguistic groups in China as their ‘own people’, they effectively psychologically minoritised themselves.

The adoption of a new identity became a key motivation for the establishment of a common language. The definition of Hàn that includes Mandarin, a much larger linguistic group, meant the demotion of non-Mandarin Chinese languages to ‘dialects’.

Hàn Nationalism in Malaysia

Identity politics in Malaysia, particularly between the Malays and Chinese, has given Hàn nationalism a new lease of life. But it is the carrying over of this nationalist ideology into their view of language, that has given rise to the view among many Hokkien leaders, that Mandarin is the de facto Chinese language.

Some of these leaders would eventually become champions for their own language to be replaced with Mandarin, in the belief that this would unite the Chinese in order to resist ‘Malay cultural aggression’.⁹

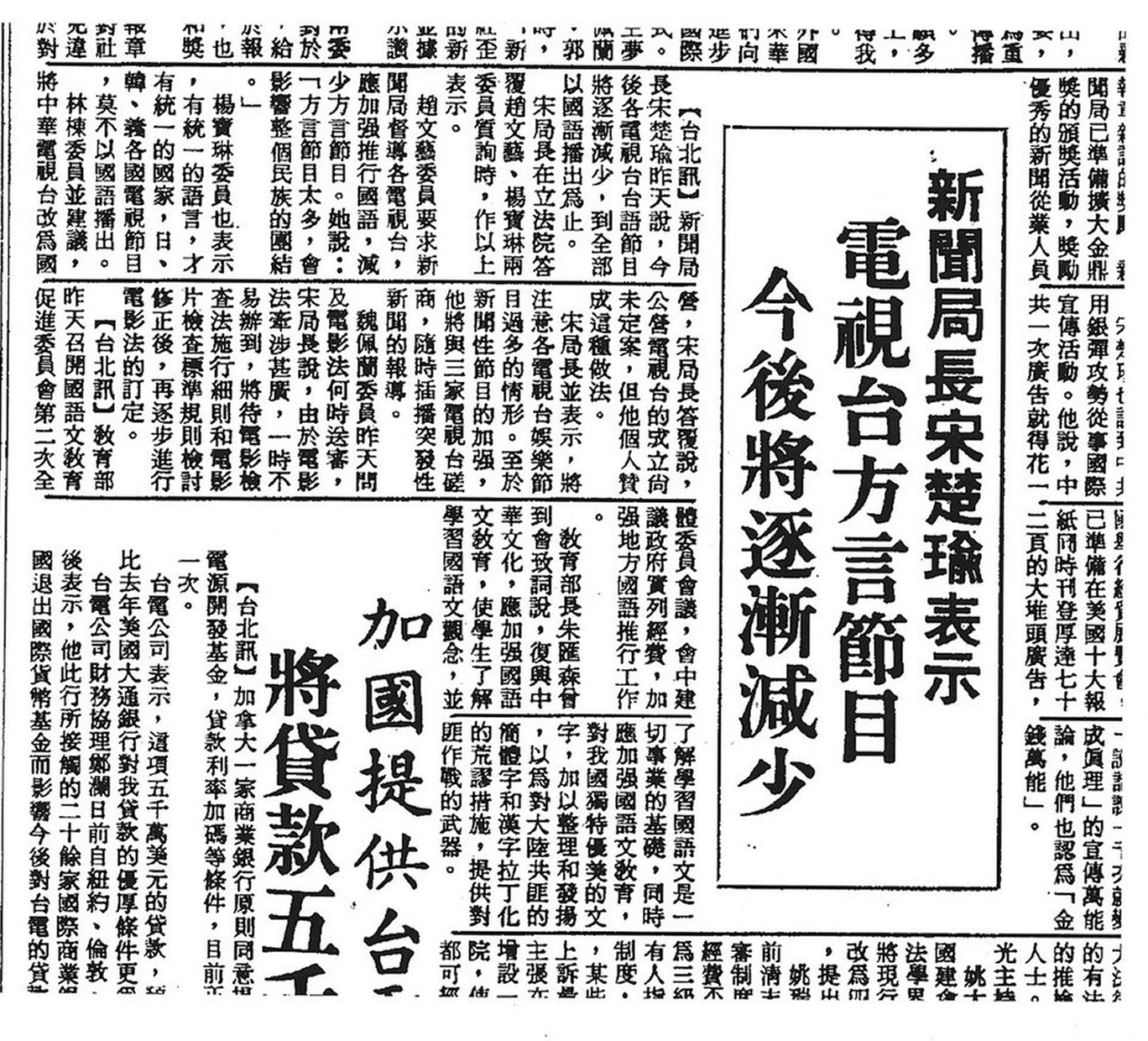

These Hokkien leaders were so enthusiastic about Mandarin that they wanted it to replace all southern Chinese languages, including Hokkien, in public broadcast.

Lim Lian Geok 林連玉 and Sim Mow Yu 沈慕羽 were two figures of Hokkien descent. Captivated by Hàn nationalism, they became prominent Mandarin education advocates, instead of Hokkien.

Further still, Sim Mow Yu 沈慕羽, who was a member of the Nationalist Party of China (Kuomintang), ran a school in Melaka. One of his goals was to replace his mother tongue, Hokkien, with Mandarin.

Lim Lian Geok

林連玉

Lim Lian Geok, a public figure of Hokkien descent, became a prominent advocate of Mandarin education in Malaysia.

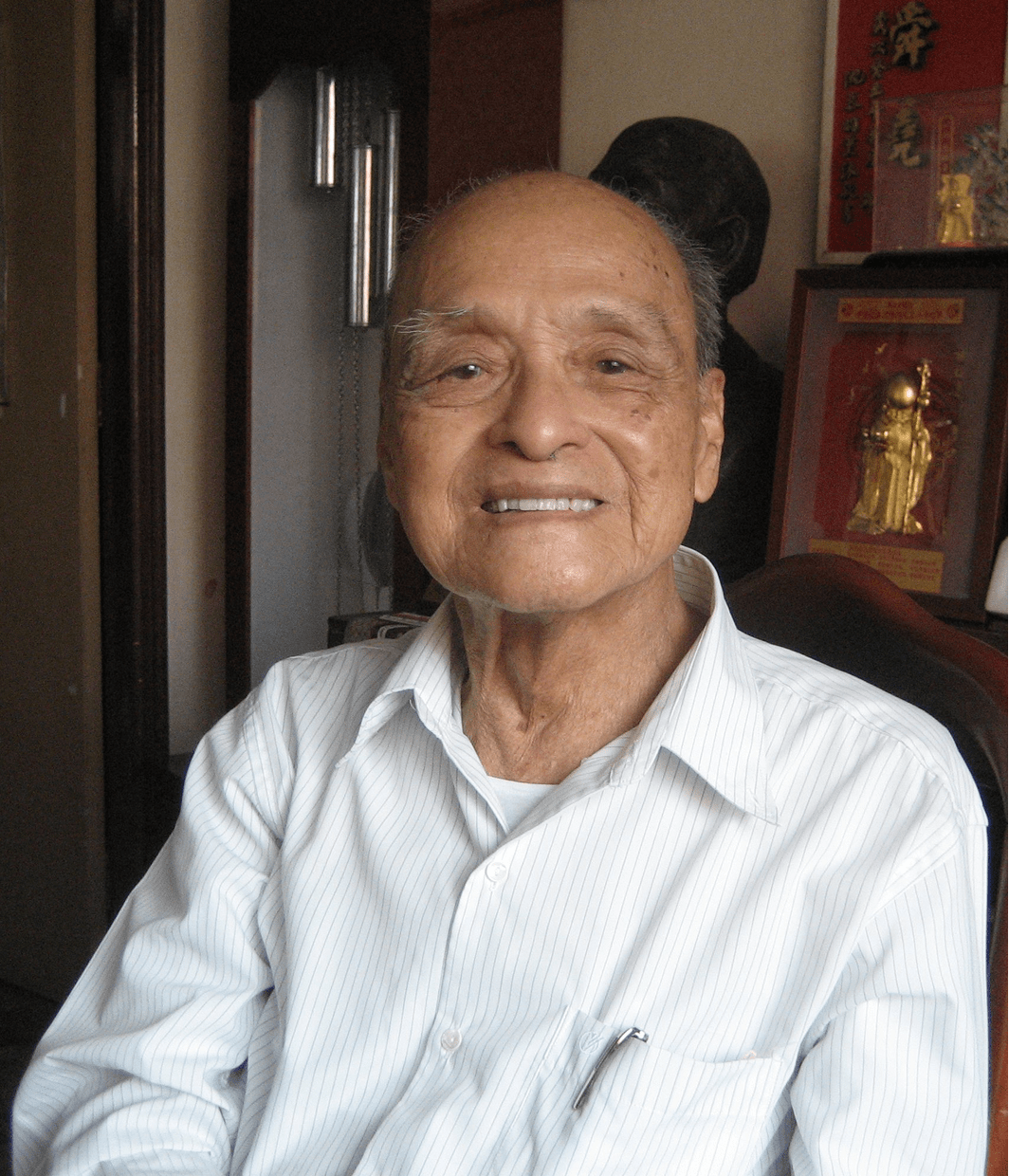

Sim Mow Yu

沈慕羽

Sim Mow Yu, a prominent Hokkien leader, ran a campaign in Melaka to replace his mother tongue with Mandarin.

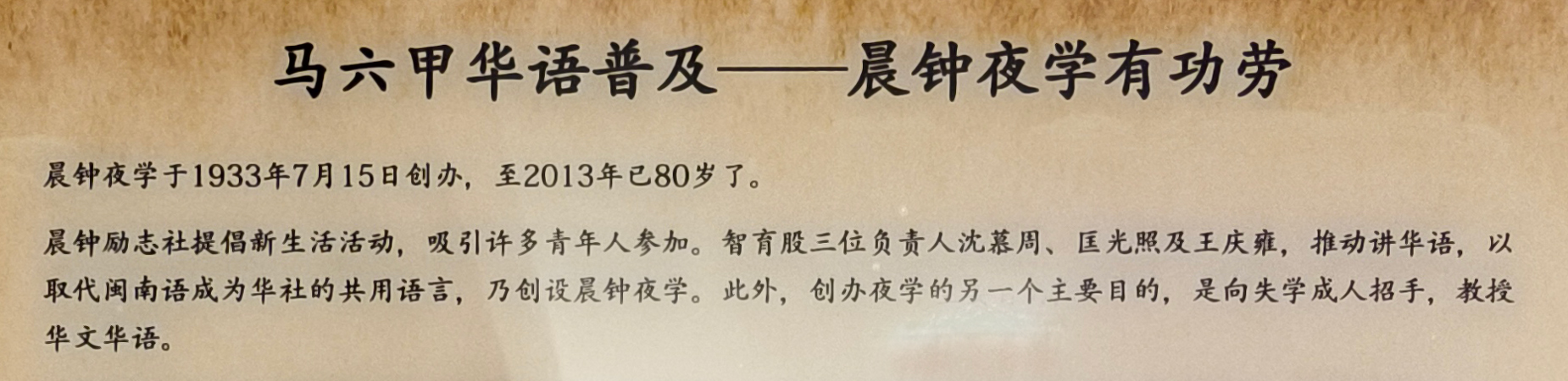

Sim Mow Yu 沈慕羽 founded Seng Cheong Night School 晨鐘夜學 to promote Mandarin and as a way to replace Hokkien with Mandarin in Melaka.

Seng Cheong Night School in Melaka run by Sim Mow Yu.

A gallery exhibition in Melaka appears to celebrate Seng Cheong Night School’s contribution in replacing Hokkien with Mandarin as a lingua franca in Melaka town.

Over the past century, the education institutions advocated by nationalists abandoned their own languages as their medium of instruction in favour of Mandarin.

While these institutions claim to provide ‘mother tongue education’, they effectively ban their own languages by punishing and fining students who speak their mother tongues.

Chapter 09

Applying Double

Standards in

Language

Classification

In linguistic classification, dialects are normally defined as varieties of a language which are usually mutually intelligible. However, there was no equivalent native Chinese word to express the same idea before the 1920s.

When modern linguistic classification was imported into China around the 1920s from the West through Japan, the native word ‘hong-giân’ (方言 fangyan) was appropriated to translate the word ‘dialect’. This misappropriation of terminology has created a conflict in its definition because the original meaning of ‘hong-giân’ 方言 was simply ‘a language of a particular place’.¹⁰

The word was traditionally used as a catch-all term for all languages that are not the language of the imperial court. Even English, Portuguese and Dutch were all referred to as ‘hong-giân’ 方言.

It would be ridiculous to continue to refer to these European languages as ‘hong-giân’ (方言 fangyan) when the word has acquired a new definition. But both popular and scientific literature, particularly those written in Mandarin, continue to use the term ‘dialect’ when referring to other Chinese languages, thus creating the impression that all Chinese languages are mutually intelligible.

The false linguistic taxonomy promoted by the Hàn nationalists.

Weaponising ‘Hong-giân’ (方言 Fangyan) to Purge Diversity

The ruling class who could speak Mandarin were the most direct beneficiaries of such a situation. By promoting Mandarin as the legitimate Chinese and relegating all other languages to dialects (or corrupt versions of Chinese), the perception that Hàn is a unitary ethnic group would be reinforced. In turn, this allows power to be consolidated by an elite few.

Sòng Him-kiâu 宋欣橋, a university professor in Hong Kong, who is a Mandarin advocate claimed that both Mandarin and Cantonese speakers belong to the ‘Hàn’ ethnicity, and therefore ‘Mandarin and Cantonese are the same language’. He also relied on the confusion in the meaning of ‘dialect’ to justify his assertion that Cantonese was not fit to be the mother tongue of the people in Hong Kong.¹¹ His remarks created an uproar in 2018.

Language Policy Driven by

the Hàn Nationalist Ideology

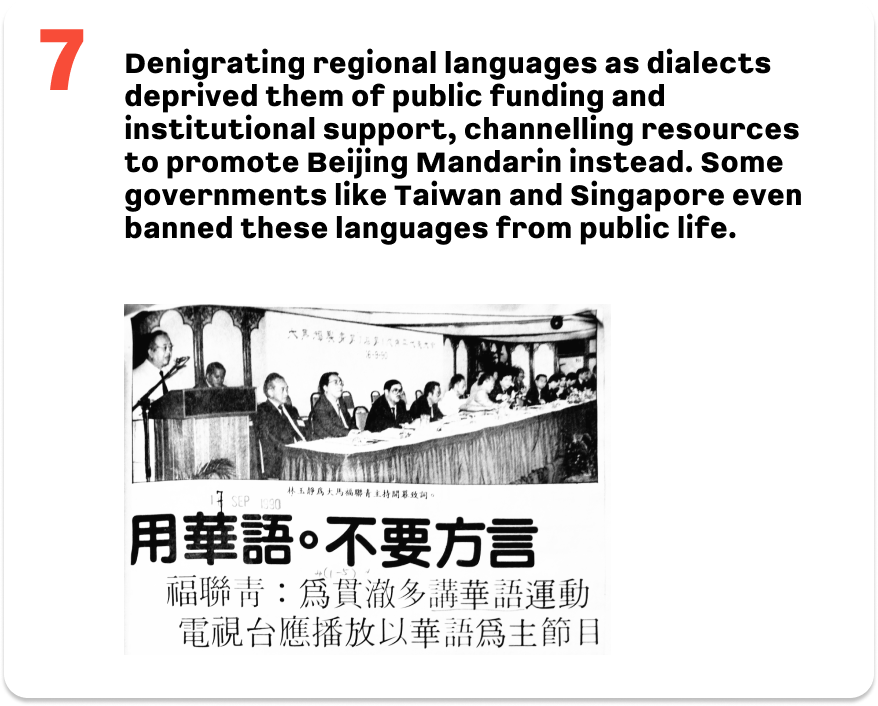

Most policies related to languages implemented in the 20th century were based on Hàn nationalist ideology. These policies were all aimed at relegating the status of regional languages and restricting the use of local tongues in public life. Some governments such as those in Taiwan and Singapore even banned them.

15 February 1913

The newly founded republican government took the view that Chinese is a single language and set up a commission to unify the pronunciation of all the characters contained in the rhyme dictionary, Subtleties of Phonology (音韻闡微). The commission (讀音統一會) employed the voting system where each province was given one vote gave Mandarin an advantage and provided the basis for its domination.

12 January 1920

During the New Culture Movement, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China issued a decree that Literary Chinese be replaced by ‘vernacular Chinese’ 語體文 to bring spoken language in line with the written language in all first and second-year classes in lower primary schools. The ruling classes captivated by the nationalist ideology made the assumption that written Mandarin was the vernacular Chinese.

May 1932

The Ministry of Education of the Republic of China published the National Pronunciation Dictionary for Commonly Used Vocabulary 國音常用字彙, the pronunciation of which was based on Peking’s Mandarin. This solidified Peking’s Mandarin as the official Chinese language.

2 April 1946

The government of the Republic of China launched the National Language Movement 國語運動 to promote Mandarin in Taiwan after establishing its rule over the island. Students were punished for speaking the local languages such as Hokkien, Hakka and the native Austronesian languages.

1953

Cinemas in Taiwan were banned from employing Hokkien narrators.

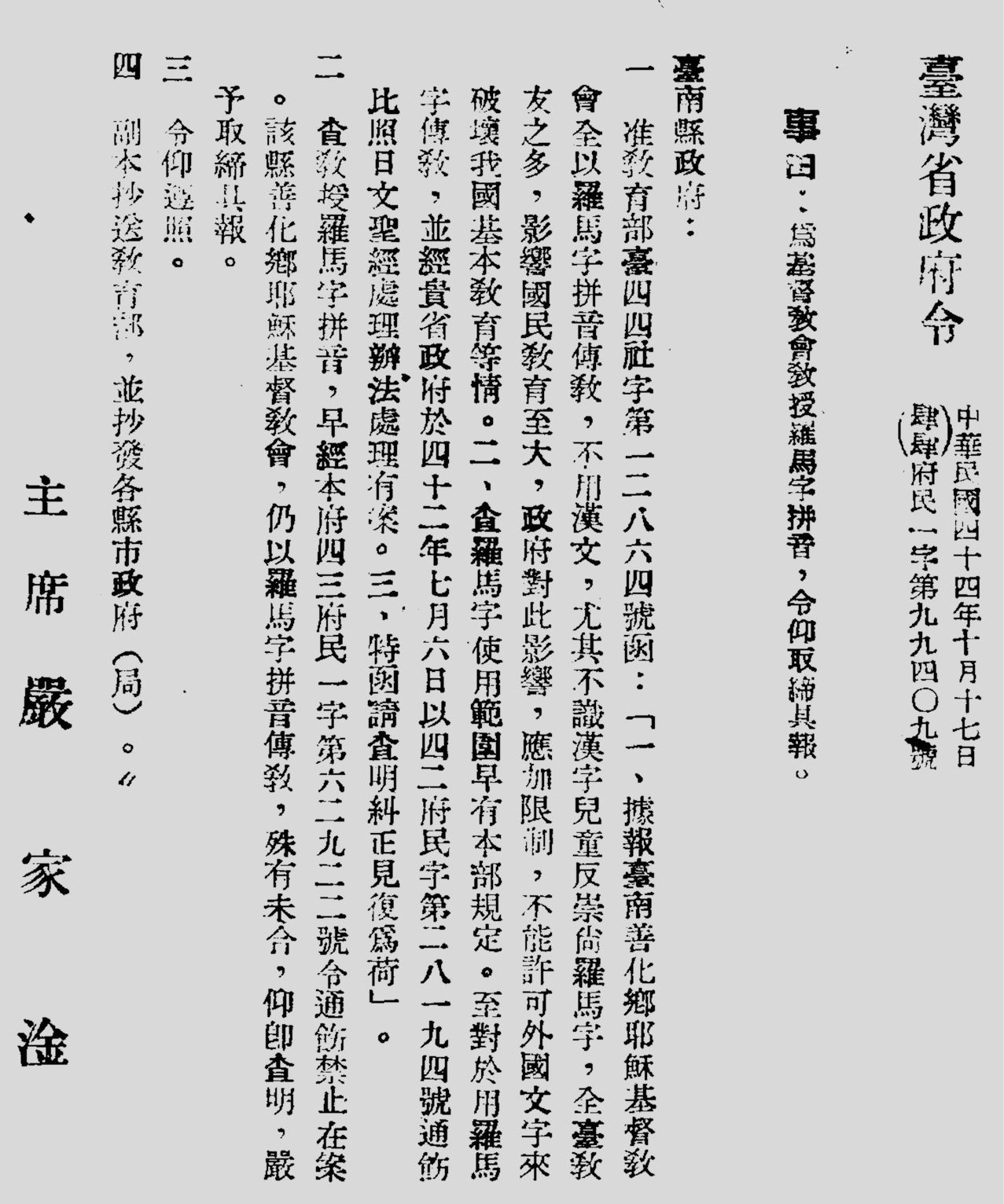

17 October 1955

Churches in Taiwan were banned from using Romanised Hokkien (Pe̍h-ōe-jī).

Government announcement on the banning of Romanised Hokkien (Pe̍h-ōe-jī).

6 February 1956

The State Council of the People’s Republic of China issued a directive to promote Mandarin and started replacing regional languages in the public domain such as education and broadcasts with Mandarin.

11 February 1958

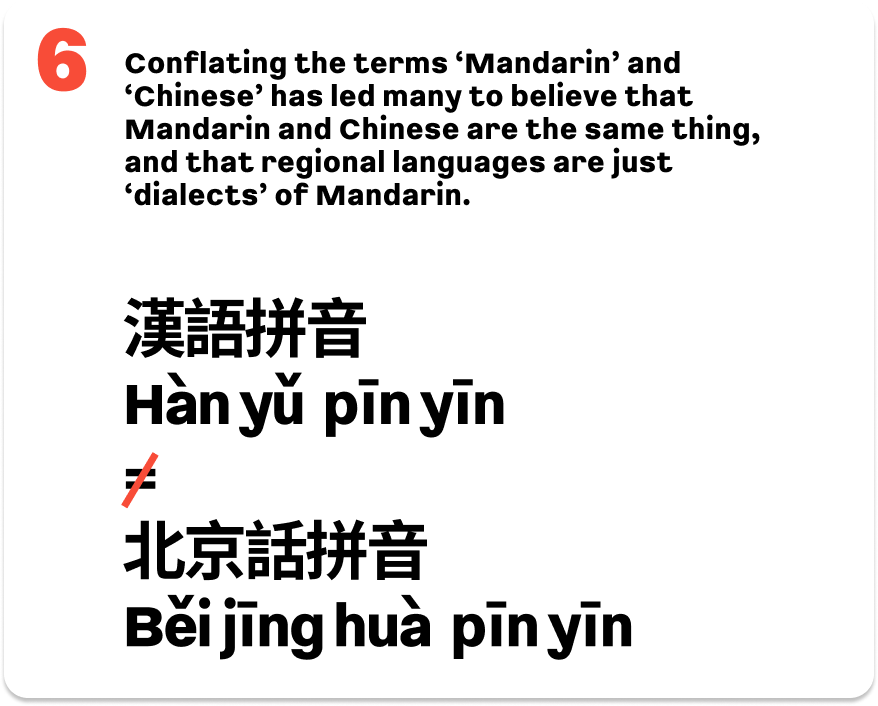

The Chinese government approved the phonetic scheme for the Mandarin language by referring to it as the ‘Phonetic Alphabets for the Hàn language’ (Hanyu Pinyin 漢語拼音). Such a name promotes the nationalist idea that Mandarin is the only Hàn Chinese language.

November 1959

Cinemas in Taiwan were prohibited from screening Mandarin films with Hokkien interpretation. Cinemas had to ‘rectify their mistakes’ or to cease operation altogether for non-compliance.

12 November 1963

The government of Taiwan issued a directive putting a cap on Hokkien and Hakka radio and TV. These were limited to no more than 50% of their total programming.

1 December 1972

The government of Taiwan intensified its restriction on the use of Taiwanese Hokkien in TV broadcasts to just one hour per day.

8 January 1976

The government of Taiwan made a law compelling all radio stations to reduce the number of programmes in Hokkien and Hakka every year.

A United Daily News report on the law compelling media outlets to reduce the number of programmes in Hokkien and Hakka.

7 September 1979

Singapore launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign. All broadcasts in southern Chinese languages are banned on TV and radio channels up until today. The campaign used several slogans that promoted the nationalist view by equating Chinese or ethnic Hàn to Mandarin, relegating other Chinese languages to patois, or corrupted versions of Mandarin. The slogans used were as follows:

- 多講華語,少說方言 (Speak more Mandarin, speak less dialects)

- 華人講華語,合情又合理 (Ethnic Chinese should naturally speak Mandarin)

- 華人 · 華語 (Chinese people = Mandarin language)

The Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979 using the slogan ‘Speak more Mandarin, speak less dialects’.

“The Speak Mandarin Campaign sought to destroy Chinese Singaporeans’ real mother tongues, first by demeaning them as provincial ‘dialects’ of Mandarin when they are in fact mutually unintelligible languages as different as English, German and Danish.”

– The Economist, 22 February 2020

22 March 1980

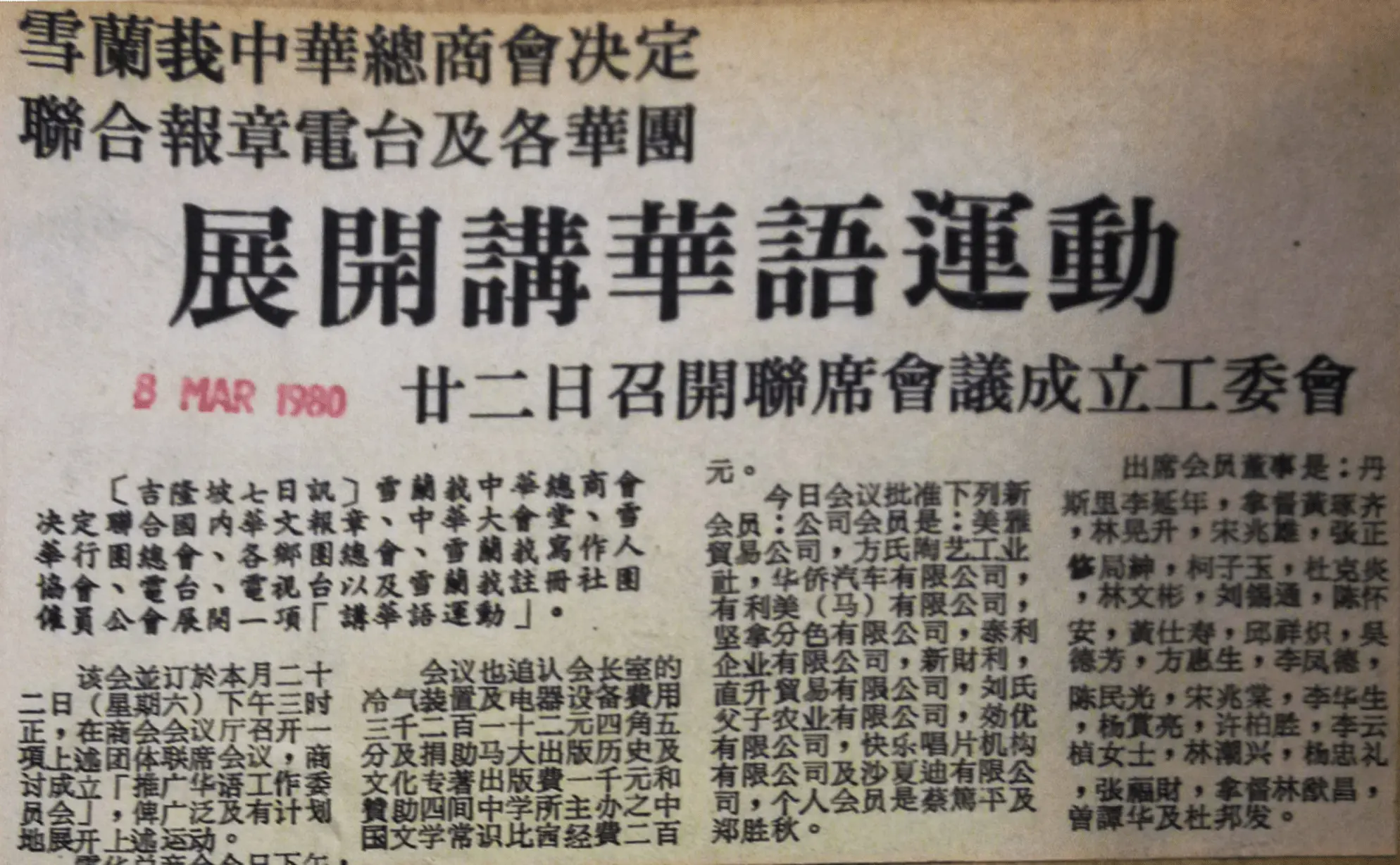

The Selangor Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry 雪蘭莪中華工商總會 imitated Singapore’s Speak Mandarin Campaign and launched a similar campaign in Malaysia. The Promote Mandarin Working Committee of Selangor and Kuala Lumpur 雪隆推廣華語工作委員會 was formed on 22nd March 1980 with the support of many newspapers and media outlets, teachers associations, including Hokkien, Hainanese and Teochew associations.

Hokkien, Hainanese and Teochew associations were influenced by the nationalist ideology and involved in the promotion of the northern language.

27 April 1980

The Government Information Office of Taiwan instructed all TV stations to reduce the number of programmes in Hokkien and Hakka every year until they completely disappeared from the airwaves.

16 December 1985

The government of Taiwan intended to pass a draconian language law to ban all conversations in Hokkien and Hakka, including any group of more than three people in public. Repeat offenders would be fined between NT$3,000 to NT$10,000.

31 October 2000

The People’s Republic of China passed the Law on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language 中華人民共和國國家通用語言文字法 to restrict the use of regional languages. Any broadcast in regional languages now needed approval from the National Radio and Television Department.

Discriminatory Slogans used by the Chinese government in promoting Mandarin:

- Speak Mandarin and be civilised.

- Speak Mandarin and be a citizen of dignity.

- Speak Mandarin, write in standard characters, be a good student.

- Establish a uniform linguistic norm and raise the quality of our national culture.

- The language of our country is beautiful. Please speak Mandarin.

‘Speak Mandarin and be civilised’ slogan in the background.

.webp)

Tsìn-kang Museum continues to promote Mandarin even though the local Hokkien language is gradually being replaced by Mandarin in its home region. (Photo by Marvin Sy in 2024)

18 October 2004

The National Radio and Television Department of the People’s Republic of China issued a directive to forbid foreign films from being dubbed into regional languages except Mandarin.

Chapter 10

How to Undo the

Damage?

Language

Vitality

The uses of a language is an important indication of its health. A language is considered healthy if the language is widely used in different domains such as education, work, mass media, at a government or international level, whereas a language is at a greater risk of extinction if it is used only amongst close friendships or only within the family.

The more a language is used in different circumstances, the more vocabulary it develops. When older generations stop speaking the language with the youngest generation, a cycle of decline begins, making it more likely that it will go extinct within one or two generations.

Linguistic

Replacement

Hàn nationalism provides an ideological basis for the export of Mandarin into the territories and domains where it had never been spoken. The ideology drives public money and private resources into developing and promoting Mandarin, leaving other Chinese languages with almost no support.

Stripping the local languages of social uses in public life and replacing them with Mandarin, particularly in the education system, has greatly devalued these local languages.

Schools set the linguistic norm of the younger generation at a very young age. Parents who want their children to do well in school are induced to speak the school’s language from birth.

Relentless promotion of Mandarin and Hàn nationalism has had, and is still having a detrimental effect on diversity.

Reversing the Policy

This is the largest and most rapid linguistic replacement of so many local languages by a single language in global history. Non-Mandarin Chinese languages will be completely wiped out in mainland China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore and soon in Hong Kong, if there is no change of language ideology and a reversal of policy.

The demise of these languages can only be avoided if they are reinstated in schools and administration, and returned to their original status as languages in their own right in their respective regions.

In the context of Malaysia, the Hokkien Language Association of Penang proposes to reform the traditional ideology that associates language with individual ancestry (lingua sanguinis) to one that associates language with a territory (lingua soli).

A special status is given to Hokkien in Penang, Cantonese in Ipoh and so on would prevent the domains of these languages from being taken over by other languages, particularly Mandarin.

If you are inspired by this exhibition, please share it with your friends and family, and consider making a donation to support us.

References

¹ Handel, Z., 2015. Dialect Diversification, Major Trends. In Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics, General Editor Rint Sybesma. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2210-7363_ecll_COM_000303

² Xue, F., Wang, Y., Xu, S. et al., 2008. A spatial analysis of genetic structure of human populations in China reveals distinct difference between maternal and paternal lineages. European Journal of Human Genetics 16, pp. 705–717.

³ 平山久雄,2002,〈從語言年代學看閩語的地位〉丁邦新、張雙慶(編),《閩語硏究及其與周邊方言的關係》香港:香港中文大學,頁4。

⁴ McLeod, M., Nguyen T., 2001. Culture and Customs of Vietnam. Greenwood Press.

⁵ 游汝杰,2002,《西洋傳教士漢語方言學著作書目考述》,黑龍江教育出版社,頁18。

⁶ Mair, V. H., 1991. What Is a Chinese “Dialect/Topolect”? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic Terms. Sino-Platonic Papers 29.

⁷ Mair, V. H., 2013. The Classification of Sinitic Languages: What Is “Chinese?”. In Breaking Down the Barriers: Interdisciplinary Studies in Chinese Linguistics and Beyond, pp. 735-754.

⁸ Chow, K., 1997. Imagining Boundaries of Blood: Zhang Binglin and the Invention of the Han “Race” in Modern China. In The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 34-52.

⁹ Sim T. W., 2002. Why are the Native Languages of the Chinese Malaysians in Decline?. In Journal of Taiwanese Vernacular, 4(1), pp. 62-95.

¹⁰ Mair Victor. H., 2003. How to Forget Your Mother Tongue and Remember Your National Language. Pinyin.info. http://pinyin.info/readings/mair/taiwanese.html

¹¹ 宋欣橋,2013,〈淺論香港普通話教育的性質與發展〉,《集思廣益:普通話學與教經驗分享》,第四輯,頁227-236。

Donate

Donate